Uniform hysteria

The weeks since 14 February 2019 – when a Kashmiri youth rammed an explosives-laden vehicle into a 78-vehicle convoy carrying about 2500 troops of the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) in India-administered Kashmir – followed by the Indian Air Force's strikes twelve days later, have been characterised by a strategic silence from the Indian state. It has, therefore, been conveniently left to the country's shrill, ultranationalist media to whip up hysteria, with its call for retribution and war with Pakistan, and the relentless propaganda masquerading as 'news'.

What has been at a premium is not just good journalism, exhibited through scrutiny over information doled out by 'sources', but basic investigation and truth-seeking. To begin with, as the media was barred from the site of the suicide attack, the scanty official information resulted in speculative headlines and imprecise news reports. For example, the death toll of the CRPF personnel varied (from 40 to 49) even days after the attack, as did the make of the vehicle that rammed into the convoy, and the nature and weight of the explosive used. When reporting of the basic facts was speculative, could the media be relied upon to investigate more complex aspects of the attack and its aftermath? In any conflict, a credible media that puts aside its nationalism is a reliable counter to propaganda from all sides. However, more often than not, Indian media seems not to have risen to the occasion.

Megaphone for the state

The media, for the most part, did not ask hard questions in the immediate aftermath of the blast. For example, what came of the intelligence inputs from the Kashmir Police, reportedly sent a week before the attack, on 8 February, to the CRPF, the Border Security Force (BSF), the Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP), the Army and the Air Force, warning them of the use of IEDs in a possible terror attack by the Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM)? Was the route properly sanitised and why were the soldiers not airlifted given the risk of potential attacks? And why was Adil Ahmad Dar, the suicide bomber, reportedly picked up several times in the past two years and then let go?

Another question that begs an answer is how did such lethal quantities of explosives make their way into the highly militarised Kashmir Valley? How could such a massive attack have been planned and executed in a region that is under the surveillance of not only the police, and intelligence agencies, but also various regiments of the Indian Army, the CRPF, the ITBP and the BSF?

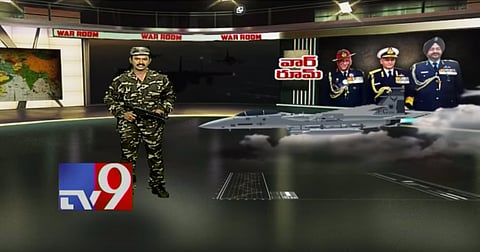

Far from seeking answers to these key questions, however, strategic silences and misinformation continues to rule in India's mainstream media. Instead, calls for revenge soon followed: "Desh maange jawaanon ki shahaadat ka badla" (The nation demands revenge for the martyrdom of the soldiers), declared the ABP News Hindi channel on 15 February, with several news channels promoting the hashtags #IndiaStrikesBack #IndiaAvengesPulwama. From the Indian tricolour fluttering at the corner of TV screens to anchors dressed in army fatigues and carrying toy guns, nationalism was not left to the imagination. The opposition parties, too, carried away by jingoism, largely failed to ask legitimate questions, demonstrating the shrinking space for dissent.

Following what India's Foreign Secretary Vijay Gokhale termed a "non-military", "pre-emptive" airstrike on Balakot, a town in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, on 26 February – supposedly targeted at a JeM camp – the casualties reported varied vastly, from 25 to over 300. While official information, relayed through Gokhale, claimed that a "very large number" of militants had been killed, satellite imagery cast doubt on the extent of the damage claimed by the Indian side. International media like the BBC and Al Jazeera interviewed local residents who pointed only to damaged trees, craters and cracks in buildings, and noted one person being injured. However, as recently as 3 March, the news channel NDTV quoted "senior officials" as saying they had satellite images proving that the target (the JeM madrassa) were indeed hit. No such images have been released till date. Whether casualties occurred at the JeM madrassa located near the bombed area is still a matter of speculation, and the Indian government has not come out with any figures yet.

Analysis of satellite imagery following the attacks – for example, by Australian Strategic Policy Institute's International Cyber Policy Centre and the Atlantic Council's Digital Forensic Research Lab – do not show evidence of the damage claimed by the Indian government. Interestingly, the JeM has admitted that its facility was indeed hit in the strike – a 'fact' eagerly embraced by sections of the Indian media, without analysis of the possible reasons for the JeM 'admission', which could include whipping up anti-India sentiments to increase its recruits.

According to Vasundhara Sirnate Drennan and Suchitra Vijayan of the Polis Project, a research and journalism organisation, mainstream media in India showed a heavy reliance on unsubstantiated information from government sources and "largely ascribed to itself the role of an amplifier of government propaganda." As they point out:

While reports regularly quote "government sources," "NIA officials" and "IB officials," these various institutions leaked conflicting information to reporters that often muddied the waters rather than bestow clarity. Also, the number of "intelligence officers" willing to disclose "classified" information speaks of a larger problem of how information from the state is conveyed and reported.

Drums of war

On 28 February, in response to Prime Minister Imran Khan's declaration in Pakistan's Parliament that the captured Indian Air Force pilot, Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman, would be released to India as a "peace gesture", some Indian media outlets refused to relent. Pakistan's move, they suggested, was a sign of surrender and Khan had, as one TV anchor suggested, "cracked under pressure". India Today headlined with "India gets Hero back, Massive Victory for India", while NewsX declared "No deal, Pak folds in fear". On 1 March, even as Varthaman was being returned to India, news channel Republic flashed: "Why de-escalate?" "Let the Pakistanis know there will be revenge. Let us not stop hitting them," declared Arnab Goswami – head honcho of Republic TV – who is among those in the media leading the charge in the cries for war. Of course, these war cries were also heard on the air waves across the border, with anchors on some Pakistani channels, too, dressed in uniforms of the defence forces and lining up hawkish ex-army officers to goad the establishment to more hostilities.

Not to be left behind, the entertainment industry also rushed to get its finger in the pie. Patriotism pays at the box office, and there is money to be made in war movies. Mumbai-based Indian Motion Pictures Producers' Association (IMPPA) reportedly saw a spike in registration of titles like 'Pulwama: The Deadly Attack', 'Surgical Strike 2.0' and 'Balakot' over the last few weeks. On 28 February, the day after videos of Varthaman in Pakistan Army's custody emerged, Ankur Pathak, Bollywood editor at HuffPost rang up the IMPPA to check if the titles 'Abhinandan' or 'Wing Commander Abhinandan', were available. "It will be gone soon," he was told, with the suggestion that he speed up his application. For a paltry sum of INR 250, a production house can block a title and later sell it off to a producer with the finances to make the film.

Social media and online theatrics are also being deployed by the state as one more tool in the war of perception. While earlier videos of Varthaman, including one where he was beaten and wounded, were taken down by YouTube on the Indian government's request, another video, likely recorded by the Pakistani military intelligence, was released on the evening of 1 March, as the pilot was being handed over the to the Indian officials at the Wagah border. His black eye from the previous day still visible, Varthaman is seen dressed in a clean and pressed flight suit, and over a clumsily edited video, calmly describes the manner of his ejection into Pakistani territory, his 'rescue' from angry mobs by army personnel, and how well he was treated in custody. Perhaps most important is when, in a deadpan voice, he says that the Indian media is inflammatory, sensationalist, and adds "mirch masala" to 'spice up' events and mislead people.

While we wait in vain for the mainstream media in India and Pakistan to report on the plight of civilians on both sides of the Line of Control and question the establishment, it is worth noting that in a propaganda video recorded by the Pakistan army, it is the Indian media – and not New Delhi – that is the focus of criticism. Whatever be their powers and capabilities, it is a telling comment on the perception of India's mainstream media and its supposed ability to foment war.