The perfect storm and the final famine

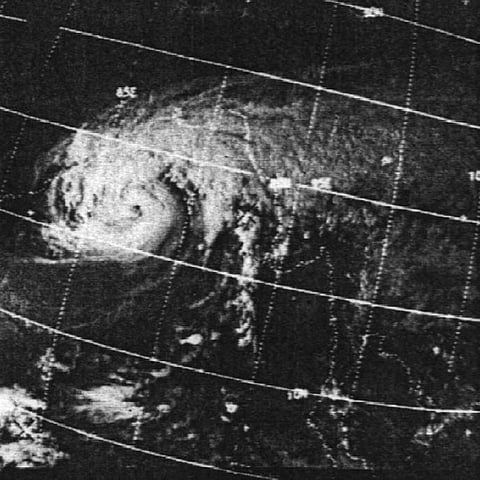

About ten years ago, the popular narrative about Bangladesh changed from the world's 'basket case' – a land of harsh Malthusian circumstances – to an awakening Bengal tiger, an exemplary, if cautionary, tale about development in globalising times. It was an unlikely trajectory. The first half of the 1970s had Bangladeshis facing what must have felt like a cosmic effort at annihilation: one of the deadliest tropical cyclones in history and a genocidal war that resulted in mass murders, rapes, and creation of refugees in their uncounted millions, destroying livelihoods, infrastructure, markets and institutions. They also endured floods and a major famine. All of this was before the human tragedy and political crisis of 1975 that gave rise to a decade and a half of military rule.

Yet only a quarter century later Bangladesh was spoken of as a modest success. It got children, particularly girls, into school; brought down fertility rates; invented micro-credit; tackled natural disasters; took effective immunization, diarrhoea and TB programmes 'to scale'. The landscape was transformed with women going to work in the export garment factories, public service or NGOs, or just going about their business – remarkable in a conservative, agrarian society. Jeffrey D Sachs lauded these achievements in his book The End of Poverty: Economic Possiblities for Our Time, with a foreword by Bono, no less. Special issues of the Lancet dissected these achievements. Bangladeshis won the Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts to tackle poverty – which has not been without critics and 'discontents', as anthropologist Lamia Karim documents in her study of microfinance, the antipoverty technology for which the country is so well known.