For really to think about someone means thinking about that person every minute of the day, without letting one's thoughts be diverted by anything – by meals, by a fly that settles on one's cheek, by household duties, or by a sudden itch somewhere. But there are always flies and itches. That's why life is difficult to live.

–Albert Camus, The Plague

His father hated him more than anyone else and always called him rang'a-tsaer; a finch. He spent his entire youth drawing, sketching and painting. Even on the day he received the gold medal in fine arts (painting) from his university, nobody in his circle of family or friends showed him any appreciation. A permanent government job in Kashmir meant much more than winning gold medals and accolades.

So after dabbling in the arts for a while, he got a government job in the arts college where he had studied. His father stopped taunting him at once. But he wasn't able to establish himself as an artist yet. He was like any other government employee, earning a reasonable salary. His immediate society was eager to see its young generation as doctors, engineers, management-professionals and bureaucrats and did not care much for writers, artists, musicians, singers and sculptors. Now, only those who doubled as doctor-writers or engineer-painters or bureaucrat-singers or management-professional-guitarists were forgiven for their artistic side. Such was the case with Irshad Ahmad Lone.

***

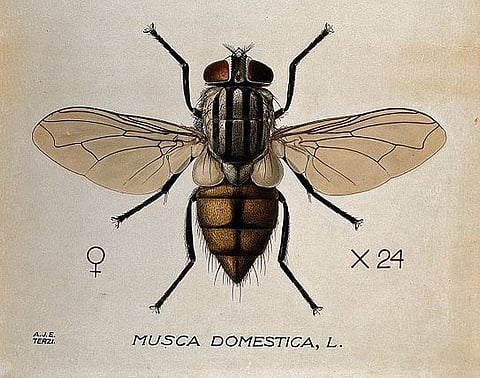

These days Irshad has been working hard on a painting to be showcased at a prominent art exhibition in the city. Since morning, his work has been disrupted by a housefly – and soon he is forced to shift his concentration from his work to the fly.

In the morning, when he went out to have tea in the kitchen, he left the door open and that is when it must have flown into his studio. Now he chases it around and tries to kill it with a rolled magazine but in vain. He also thinks of opening the windows but that could invite other flies. Unbidden, a memory pops into his head: he remembers the chowk outside his house, always crowded with hawkers and pedestrians, before an army bunker had come up. Within months, he was surprised to find the bunkers and troops outnumbering the locals and their stalls; not just in the chowk itself but the entire neighbourhood.

Irshad felt irritated. Resolutely blanking his mind, he stared at the arrangements in the studio – colours scattered all over the floor in little bottles, tubes and tray palettes, canvases, easels and some unfinished work, still wet with colours. It made it all the more difficult for him to move around.

Suddenly, the fly becomes the central focus in his world of art. In the beginning he takes it easy and at one point he even gives up chasing it but the fly returns shamelessly and settles on his painting-in-progress – a surrealistic representation, themed, "fragility of art itself…of the tussle between the power of art and the art of power", inspired by the work of Salvador Dali. In his messy yet colourful art career, Irshad began with simple impressionistic caricatures of his surroundings, depicting the slow movement of curfewed life in the Kashmir of 1990s; tiny brushstrokes and the full use of light and shade portrayed his themes of "desolation outside and the misery inside". In those years, he occasionally would paint fauvist portraits of popular political leaders like Sheikh Abdullah; the pioneer liberationist Maqbool Bhat; the senior separatist political leader Syed Ali Geelani; the heroic insurgent commander, Ishfaq Majeed, and many others, limning all of them in mismatched strident colours and shadows, in the ways he understood them. In late 1990s he had moved to cubistic still-life and portraiture, breaking and reassembling them in the most abstract ways he could, to look at them from disparate persepectives.

Then he gradually turned towards expressionism, subjectively and manipulatively, painting the same things he had been painting for years, but not breaking them up, nor emphasising them in sharp colours but simply focussing on their emotional tenor. He spent quite some time as an expressionist but in the last few years he had stylistically embraced surrealism. Yet, as he moves forward with his more fantastic pieces, for some reason, he is considering reverting to expressionism.

***

The fly lands right at a pivotal spot in the painting, clipped on a colour-smeared easel, where the inextricable mixture of yellow and black brushstrokes at the base of the painting depict a man's head, which also looked like a vase when the eyes shift their focus. The head looked melancholic, glancing sideways; hands with mutilated fingers, stemming from the scalp of the head, blossomed into some strange flowers whose petals are elongated teardrops around carpals made of eyes.

The colours on the canvas are still wet. If the fly crawls about it, the painting will certainly be ruined, he thinks. Irshad settles for sacrificing the spot where the fly must be hit or squashed. The spot can be redone later. Irshad hits the spot but when he lifts the rolled magazine – sticking to the wet paint – off the canvas, there is nothing except an impression of the violence in the shape of the magazine's rolled, cylindrical outline. The fly still buzzes around under the ceiling. Indignantly, he grimaces and grumbles around the studio for a while and then leaves carefully shutting the door behind him.

***

Later in the day, to distract himself from thinking about the fly, he decides to visit the hotel on Dal Lake's edge, where the exhibition is to take place. He feels enthusiastic, imagining where his painting would hang in that clean, untrampled space.

But on the way, the only thing on his mind is the housefly. Despite repeatedly scanning each and every corner inside the bus that he boards from Lal Chowk, he is baffled to find no housefly. Yet, as the bus trundles along the shore of the Dal, he finds hundreds of flies swarming around a heap of garbage at Dalgate. Is my painting also garbage? He thinks, and is embarrassed within. No, even sweets are thronged by flies. At Nehru Park, he observes that the vendor selling watermelon slices on a pushcart is under attack, with dozens of flies dive-bombing into the fruit platters.

The gallery in the hotel is cool, large and silent. He notes that there are no flies here either. He carefully examines the ceilings, the corners, the chandeliers… everything. But finds nothing. In a while he meets the curator of the hall, who looks bemused when Irshad questions him about the absence of houseflies.

Was the gallery free of flies, despite the hotel being so close to the weedy lake?

The curator confirms that the gallery is fly-free.

Do they use any poison? The electric insect-scorcher?A lethal gas or smoke? Anything else?

"It is not an issue at all," the curator says, a little baffled.

In everything about his work, his earlier paintings, his ideas for future work, Irshad sees a dirty fly buzzing and hovering relentlessly. His earlier work on impressionism and attempted emulations of Picasso – all swarming with flies.

***

Back home, the fly refuses to vacate his mind or his studio. How did something so insignificant, so very irrelevant, shamelessly and insidiously creep its way into my creative life? If it knew only its own futility against what it disturbs, against what it doesn't let happen, against what it ruins, it would die of shame. But the triviality of its own existence wouldn't let it, he mutters in the direction of the fly, which continues to buzz under the ceiling with great indifference.

Irshad studies the fly's prominent brown eyes as it rests for a moment on his right hand's little finger, as if contemplating its next flight. After some time, he quietly places a poison-filled tray on the floor of the studio and reclines on a worn out couch in a corner, waiting, and imagining the fly landing in the tray and flailing its legs while dying in it. He is exhausted, physically and mentally, and has rejected the idea of using a poison spray. That could harm the colours on his paintings, which are yet to dry. Soon he falls into a deep slumber and dreams: he is absorbed, giving final touches to some iridescent object in a painting, which is a life-size portrait of some creature. And while he is moving the brush, hundreds of flies whir around the painting.

Sometimes in his sleep, in the dream, he feels a ticklish crawl over his bare arms, feet and face. He wakes up crying like a child. He looks at the tray and does not see the fly in it. But he can still hear that deeply agonising intermittent bumble somewhere in the room.

Of such a wicked creature, he has never been so conscious in all his life. No flying creature is as shamelessly stubborn as a housefly. Not a mosquito that you could shoo away and it wouldn't return too frequently to sting you. It might extract its drop of blood from you, get its thorax heavy with it and then hide itself and brood quietly in some crevice the whole day. The weight of the liquid load of food it carries slows down its flight and makes it vulnerable to death. You could easily clap it dead if your eyes had chased it well. Moths were genuinely disturbing, blind and hell-bent on their own suicide. They soon left their bodily trappings, unlike houseflies that were always reluctant about leaving. The bee, unlike all flying insects, was always in a purposeful hurry. Without wasting time, a bee would bumble about for a moment, unsteadily making their way to the most fragrant flowers, before taking off with their souvenirs of nectar. But housefly is different – shameless and useless.

After sometime Irshad falls asleep again and finds himself in the exhibition gallery. People have come from far-off places; elite men and women from the art world, lovers of paintings and even some business doyens are there to see and buy paintings. His latest creation, a large, exquisitely framed painting, is conspicuously visible among the works of art hanging close to the entrance of the gallery. People stroll past the paintings, stopping at each, commenting and appreciating the work displayed.

Irshad is standing in front of his painting, smiling at a group of art experts who are trying to figure out why such work has been allowed into the exhibition. Irshad is curious about the dismissive experts, so he turns his head to see what might be upsetting them in his surrealistic painting of head, hands, fingers, flowers, eyes, tears and other objects. But he is surprised to find that behind him is a simple impressionistic painting he has never wished to paint – a life-size housefly in broad daylight.

He wakes up, feeling an itch on his skin. He finds no fly in the poison-filled tray. Absolutely frustrated and sighing heavily, he finally decides to open all the windows to let the solitary fly out. A couple of minutes later, he finds houseflies buzzing everywhere in the studio.

~ Shahnaz Bashir's debut novel is The Half Mother. His short fiction, memoir essays, poetry and reportage have been published in A Clutch of Indian Masterpieces: Extraordinary Short Stories from the 19th Century to the Present; Of Occupation and Resistance–Writings from Kashmir, The Caravan, Fountain Ink, and Kindle, among others.