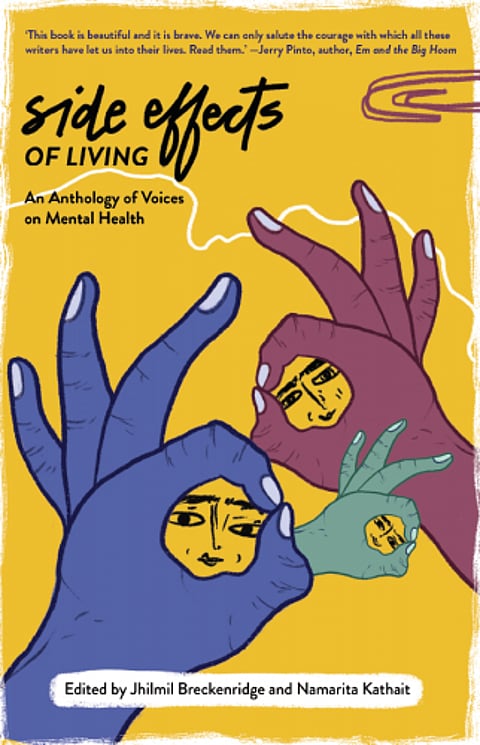

From the cover of 'Side Effects of Living'. Illustratin and design by Sonaksha Iyengar.

Learning to Live in Non-Consensual Reality

By Jayasree Kalathil

Reflecting on why he became a writer, the Nigerian novelist, Chinua Achebe said in an interview in The Paris Review:

There is that great proverb—that until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter. That did not come to me until much later. Once I realized that, I had to be a writer. I had to be that historian. It's not one man's job. It's not one person's job. But it is something we have to do, so that the story of the hunt will also reflect the agony, the travail—the bravery, even, of the lions.