Scoping the bigger picture

The trepidation was palpable on the opening day of Chobi Mela. There it was again, against all odds. One of the most important photo festivals in the world, Chobi Mela has been a remarkably regular feature since its opening edition in 2000, welcoming guests every other year to Dhaka in spite of Bangladesh's many political upheavals. Yet there was a worry that this year it might finally have to bow down and go quiet. Shahidul Alam, a photojournalist and the festival's founder, had been in jail for more than 100 days for his remarks on student protests in Dhaka, and was released on bail barely three months before the festival was due to open. What kind of a festival could possibly be scraped together within this short time frame?

Fast forward to 28 February 2019, and the opening rally of Chobi Mela was packed with guests. Alam's sharp introductory speech left no doubt about the organisers' intentions. "You are an artist, you have no business in politics," he recalled being told in detention. "And yet the role of photography is to show the truth to power," Alam said. The festival would serve precisely that purpose – there would be no going quiet.

Raw language

Still, the festival bore some of the brunt of the recent political storm. Whereas past editions of Chobi Mela had been held at the Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy, a gigantic exhibition space in the heart of Dhaka, the government-owned building was not available to the festival this year. Neither was the Ministry of Cultural Affairs a patron this time around, like it had been in the past. But the organisers were keen to see this as an opportunity. Shunning the usual polished 'white cube' mode of presentation would allow for greater experimentation this time around. Under an ethic of improvisation, Chobi Mela would be "a much more raw and community-oriented festival," Alam declared before the opening.

Exhibits were scattered among venues located in and around Dhanmondi, a leafy residential area not far from the city centre, where the proximity of several private universities guaranteed a steady supply of students. A building under construction served as the Mela's main venue – a bold choice. Displayed on four floors of the building – amid heavy-work equipment and raw concrete walls repurposed as exhibition space – the photographs and artworks on display acquired a certain urgency, which no sophisticated display could tame or dilute.

New ambitions

For the second edition in a row, Chobi Mela dedicated a section of its exhibition to a group of young artists with a mandate to push the boundaries of the medium of photography. Over a dozen Chobi Mela Fellows with widely different backgrounds – from painting to architecture to coding – showed their work in an exhibition curated by Zihan Karim, a Chittagong-based artist and educator. Among these, Ashfika Rahman's 'Files of the Disappeared' stood out the most.

On a large, wall-sized screen, successive images of paddy fields and lush forests stood empty under darkening skies. In front of it, light-boxes on pedestals showed various subjects, mostly men, mostly alone, standing or sitting in non-descript domestic backgrounds, their gazes turned towards the exterior of the frame. On some photos, the artist had stitched the subjects' mouth shut with a golden thread. On others, entire faces were covered. This was Rahman's way of addressing the recent history of enforced disappearances in Bangladesh. "More than 4000 young people have been picked up randomly by the police in recent years," read the caption. "They were tortured in custody. Some came back, but they are not allowed to speak out".

The simplicity of the work was what struck most. With their empty landscapes – places, as it turns out, where some dead bodies of the 'disappeared' had suddenly resurfaced – and indifferent décors, these otherwise unremarkable photographs inevitably pointed towards a remarkable episode in the recent past where young people had vanished for no apparent reason.

"The first thing that came to my mind was fear," Rahman explained about her work. "Fear is the most unexpected obstacle that is killing our generation from inside. I was trying to dig that fact." But Rahman's work is not intended only to serve as documentation – it has wider ambitions. The collaborative work between her and the subjects of her photographs also included post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) tests and mental-health counselling – a process that according to her "can also be considered as healing process." In spite of these cases being specific to Bangladesh, Rahman stressed how she saw the authoritarian threat as a wider concern about public freedoms.

Photography as shifting terrain

Another thematic pillar of the festival was photographic archives and the role they can play in education. Traditionally, archives are seen as a repository of memory. Yet, as one speaker in the festival noted, they are also "the place where the past is created for the future." With all sorts of memories being politically weaponised across Southasia, archives are the terrain of choice for powerful actors to fight their ideological battles over. Conversely, as it happens, they are also a place in which to push back against the powers that be.

One good example of this were the works of Kashmir Photo Collective, presented as part of the 'Archives of Persistence' exhibit. An installation of dozens of apparently innocuous photographs – newlyweds posing in a studio, a group of students surrounding a beloved teacher, a family outing in a mountainous landscape – with one image at the centre that was concealed by a blank sheet.

of Persistence'. Image by Sarker Protick / Chobi Mela

"Narratives of tourism and then war have hijacked the Kashmiri past," said Alisha Sett of the Kashmir Photo Collective. "We wanted to give the people of the valley their voice back. We collected their personal images, often from family albums, and we talked about it with them. These photographs allow us to see Kashmir anew." Indeed, the tranquility of the series appeared all the more poignant in a week that saw vociferous sabre-rattling between India and Pakistan.

But what about the covered image, then? "The image shows Salman Rushdie visiting the valley in the early 80s, shortly after the publication of Midnight's Children," Seth said. This was years before Rushdie's life was threatened by Ayatollah Khomeini's infamous fatwa, following his 1988 novel The Satanic Verses. In a striking illustration of the shifting sands on which images are read, understood and reinterpreted, Sett continued: "This photography cannot be shown because the people who were with Rushdie at the time would become targets today."

Sher-Gil, Paris, France, May 1931′ by Umrao Singh Sher-Gil. Photograph courtesy: The Estate of Umrao Singh Sher-Gil / PHOTOINK / Chobi Mela

Another exhibit on the same floor continued this reflection on the 'truthfulness' of photographic archives. The short but compelling selection of five bodies of work shown in 'Solarised' proposed to examine "one of the most authoritative and yet anomalous artifacts that were to enter the archive – the photographic image." In the process of archiving, the curators claimed, the nature of the photographic image – and, with it, of the archive as a whole – had changed irremediably.

The archiving process incarnated in its most mundane gesture – the scanning of documents – had reversed the ability of photography to capture light and therefore to record events 'objectively'. Instead, it was now the printed image that was subjected to light and, later, to further editing on screen. As the exhibit noted:

image gets converted into pixels that are beamed back to us on our liquid crystal display (LCD) monitors. This is happening to millions of photographs from different archives all around the world that are being digitized today… The archive has changed… We don't yet know what the effects shall be.

Eerie, double-exposed portrait studies by Umrao Singh Sher-Gil and the conceptual series by Shilpa Gupta both cleverly mused on this theme of photographic reproduction. But it was the re-impression of old, damaged black-and-white studio photographs that arguably gave the subject its most potent illustration.

Artist Mohammad Hasan Zobayer had resuscitated the works of Biswasnath Das, a 'mofussil photographer' active in rural Bangladesh in the 1960s. Vicissitudes of time and poor storage conditions had damaged Das's films. But the marks, spots and traces only added to the poetic quality of the images. Once again, the subjects did not appear striking: young men posing in a studio, a frog on a table, a dog climbing on a chair. What the photographs were really about was instead the complex nature of the image and the nebulous, sometimes conflicting intentions of those who create images. As Alam said, during a talk on mofussil photographers later in the festival, "Film was an expensive commodity in then East-Pakistan. And yet some studio photographers went further than what people would commission from them. They took pictures of what they found interesting and we, in turn, can only try to understand what they wanted to achieve."

The politics of memory

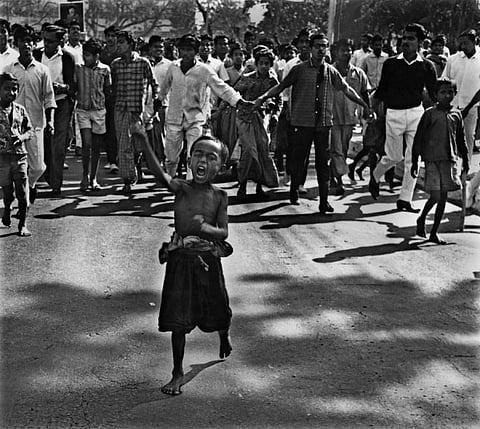

That the work of Biswasnath Das was accessible at all is a testament to Chobi Mela's resolve to account for and showcase Bangladesh's photographic heritage. 'Rashid Talukder: A Life's Work', a special exhibition at the festival, conveyed the same point. A photojournalist whose work is inextricably woven with the founding events of his country – and for which they are sometimes the only available documentation – Talukder shot some of the most iconic images of Bangladesh' struggle for independence: the street boy leading the crowd in a 1969 mass protest, the all-women platoon of would-be freedom fighters, the severed head among bricks in a pool of mud.

Yet behind the revisiting of a genial career laid a more subtle message. "Nothing daunted him, neither police beatings, nor the lack of institutional support or the fear of risking his own life," writes Munem Wasif, curator of the exhibition, about Talukder. A caption in the same exhibit next to an image showing the police beating protesters wittingly reads "some things never change". The jibe should not be over-interpreted, yet this would have been unthinkable in a public museum.

Talukder's oeuvre rightly belongs to the officially sanctioned history of his country. Yet it is essential that works such as his, despite their closeness to authorised national narratives, be seen in spaces that are as free from political interference as possible. Because of their independence, Chobi Mela and other like-minded platforms play a vital role in showing an uncut, unsanitised version of the region's history – and in reminding us of its troubling tendency to hiccup.

Finding solidarities

The collective concern about the erosion of public freedoms, at regional and global levels, was perhaps the festival's most consistent feature. During the festival's very first discussion, titled 'Freedom of Thought and Expression', the panelists offered a bleak assessment of the current state of civil liberties in Southasia. Nurul Kabir, editor of New Age, a Dhaka-based daily, observed that countries in the region were towards the bottom of the Press Freedom Index, which he said was "a direct threat to the idea of a deliberative, participatory democracy."

Worse, insidious ways of diluting critique have appeared. In some cases, there are strong financial motives behind this trend. According to Tanvi Mishra, the photo editor of the Delhi-based magazine Caravan, who was part of the panel, large sections of the media, particularly broadcast media, don't question those in power anymore because of the way these organisations are funded, and the relationship between the funding and the establishment. The editor of the Kathmandu weekly Nepali Times, Kunda Dixit, noted, "Now that the mass media is under control, the next target is social media," highlighting laws that constrict freedom on the internet. But he also added that this trend wasn't new. "The question is: what do we do about it?" In the process, the discussion laid bare a central feature of the festival: a platform chronicling public freedoms at various stages of decay; it would also aim to devise new ways of action.

One idea that came up as a possible response to the emerging authoritarian trend was transnational solidarities. After all, Alam had just been freed on the wave of an impressive international mobilisation, which proved that the cause of an imprisoned activist was not necessarily a lost one. Yet many also remarked that governments and other powerful actors had devised more efficient tactics to silence dissenting voices: smear campaigns, cuts in revenue, or administrative strangulation, among others.

Several practical solutions were suggested: having shared back-offices to free smaller institutions from draining administrative work; holding cross-pollinating events across the region; building networks to devise long-term policies to avoid ad hoc responses inevitably generated by each emergency. Only time will tell if and how these ideas will be implemented. But the fact that they could be discussed at length testifies to the need of platforms such as Chobi Mela.

What was Chobi Mela and what happens next?

Despite continuities in the spirit of activism and resistance that has characterised Chobi Mela over the last two decades, there could be no hiding from the fact that the festival has changed tremendously in the last 19 years. 'What Was Chobi Mela and What Happens Next', a project by artist and historian Naeem Mohaiemen, proved just so. Going through past catalogues, Mohaiemen showed the evolutions and ruptures in the festival's history. The backbone of the festival's early editions, works of documentary photography have more recently cohabitated with experimental works in various media. The Mela's exhibitions in recent years gave room to widely different practices, showing the works of veterans of documentary photography alongside conceptual propositions by young local artists. The festival's "fever of fighting inequality through camera", Mohaiemen noted, was now complemented by a turn towards autobiography, abstraction and surrealism. Having started as a photojournalism festival high on values, Chobi Mela is now a hybrid platform high on values.

This raises the question of what the festival should aim for. The content of future Melas will continue changing; as Mohaiemen reminded, it has to change to reflect the shifts in the world of photography. The format, too, will evolve. But its success will depend on keeping true to its founding principles, something Chobi Mela has been doing successfully.

In the days after the start of the festival, the echo of Alam's words of defiance in his inaugural speech had begun to somewhat recede. Visas had been granted and no show had been cancelled. Everything was happening according to plan. Was all this talk about solidarity and keeping power in check a bit removed? In the early hours of 5 March – the day a conversation between Arundhati Roy and Alam was scheduled – Chobi Mela's social-media streams signalled that the Dhaka Metropolitan Police had just withdrawn the permission to hold the evening talk at the designated auditorium, citing "unavoidable circumstances". Hours of confusion ensued, with an alternative venue being announced then cancelled again for the same "unavoidable reasons". In the end, the discussion did take place. But no one had any doubt anymore about how closely Chobi Mela was being monitored.

***

~Disclaimer: At this year's Chobi Mela, Diez was the moderator of a panel titled 'Balancing Power', in which our editor Aunohita Mojumdar participated.

***

More readings:

Sewa Bhattarai on Nepal's feminsit movement as documented by Photo Kathmandu 2018.

Alisha Sett's long-form profile on Shahidul Alam.