Romancing the self

| Romancing with Life: An autobiography by Dev Anand Penguin/Viking, 2007 |

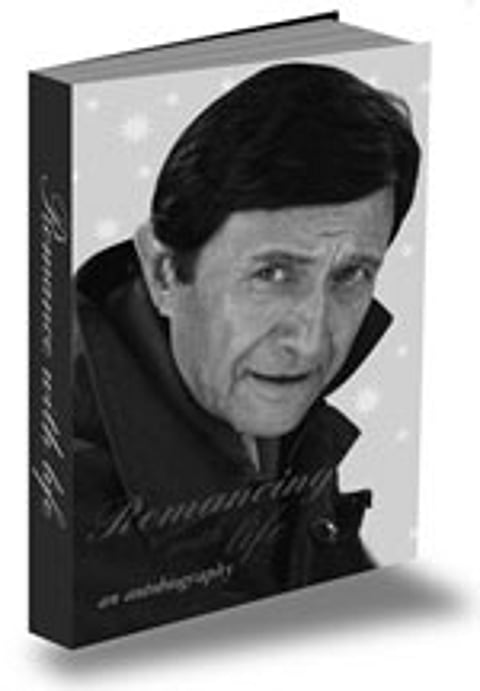

Dev Anand has always been better known for his wigs than his films, his looks than his talents, and his mannerisms than his acting or directing abilities. Likewise, his newly released autobiography can be fairly judged by its cover. The dust-jacket displays an imposing colour mug-shot of the actor, in a new toupee and his trademark attire. He is surrounded by tiny silver stars; apparently, he considers himself quite the superstar. And that about sums up the content of the book, as well: it is a story of Dev Anand's obsession with himself. If you are not a diehard fan, there is little reason to even open the tome.

The very first paragraph of the first chapter opens with six I's and eight me's. An autobiography is by definition self-centred, of course, but it is rare that a writer says almost nothing else. But, like most of Anand's films, his book too will probably be forgotten, once the current series of 'launching ceremonies' are over. In October 2007, Amitabh Bachchan unveiled Romancing with Life in Bombay. In December, actor Cary Grant's wife released it at Marawha Ranch, in Malibu. And in early May, the celebrity looked contentedly on as India's new Ambassador to Nepal, Rakesh Sood, launched the volume at an educational fair in Kathmandu.

Controversial tycoon Srichand P Hinduja's association with Anand's most famous film, Guide, is already well known. But the source of money that funded his adventure with the genre of works that includes Ishq, Ishq, Ishq has always been something of a mystery. Even today, Anand apparently has no dearth of financiers, despite the fact that hardly any distributor will touch his productions. After Hare Rama Hare Krishna in 1971, none of his films has been able to make a mark on either the critics or the box office. And yet, Dev Anand goes on making films, the latest of which was 2005's Mr Prime Minister. While rumours abound that 'non-commercial' financing sources allow him to do what he fancies – rather than being bound by what will pass the muster of Bollywood distributors and mass audiences – he says nothing in this book to either confirm or deny such allegations.

Reinforcing the adage that there is no smoke without fire, a Kathmandu-based journalist recently confided to this writer about a conversation that he had had with his Doon School junior in the early 1970s. Back then, Rajiv Gandhi was an Indian Airlines pilot who helped out 'Mummy' in whatever way he could. During one of his regular runs to Kathmandu, Gandhi complained that he was quite bothered about the 'anti-Indian' feelings he encountered in the streets. The journalist claims that he subsequently suggested that the Indian state unleash Bollywood stars to fight the war of image in Nepal. There is no reason to doubt this story. After all, the interrelationship between the propaganda machinery of Foggy Bottom and Hollywood has long been widely known. Thereafter, the role that Dev Anand may have played in cultivating the royal family of Nepal, and building relationships with the media of Kathmandu, can only be a matter of conjecture. Many speculate that the Indian government may have funded Hara Ram Hara Krishna to improve India's image.

Assigned to the north

In the late 1960s, it was widely believed that the Bollywood trinity of Dilip Kumar, Raj Kapoor and Dev Anand each had their own sphere of influence, which corresponded with the domestic- and foreign-policy goals of the central government. With his voice and presence, suave Yusuf Saab (Dilip Kumar) appealed to the Urdu-speaking audience at home, and commanded the respect of Muslims abroad. The antics of the comical Raj Kapoor tickled even South Indians and Eastern Europeans, who did not need to understand the language in order to laugh at his on-screen follies. For his part, Dev Anand's meticulously cultivated carefree image was most suited to the hills of the Northeast and the North Indian plains, where the tradition of honouring the accidental vagabond held sway.

Indira Gandhi had acquired a deep understanding of the usefulness of the film industry during her days at the helm of the Information Ministry. She successfully employed filmmakers for propaganda purposes at the time of the abolition of the Privy Purse, the nationalisation of India's banks, the Bangladesh War of Liberation, and in later years during the insurgency in Punjab. Her machinations, however, failed to deliver during the dreaded State of Emergency of 1975-1977.

Anand recounts that he had a difficult time convincing Indira Gandhi's propaganda-in-chief that 'free will' could not be forced. For refusing to attend jamborees organised by Sanjay Gandhi, for instance, Kishore Kumar was proscribed from the government media, which held a monopoly over the audio-visual medium at the time. In the West, the connection between artistes and intellectuals on the one hand, and spooks and defence planners on the other, has often rankled the press. But Southasians tend to accept such links as manifestations of patriotism. Southasian cinema – and cricket, for that atter – celebrates jingoism. Indeed, a clever display of patriotism could well be a bigger draw at the box office than the much-maligned nudity on screen – or in the stadium by cheerleaders.

Obsession with the self and the exploits of the past apart, Dev Anand has little else to offer in this meandering story. He goes to beautiful locations to shoot, but talks more about himself than about people and places. He is charmed by his own imagination, determination, decision-making – and, oh, wisdom. But nothing pleases him more than making or rejecting advances vis-à-vis beautiful ladies; from a co-passenger on the bus to a nurse in hospital, they are all evidently smitten by this desi Gregory Peck. In this way, all of his leading ladies, from Suraiya to Tina Munim, appear as mere props in Romancing with Life. It is only Zeenat Aman who makes the author admit that others, too, are capable of taking their own decisions.

These days, most barely even notice the films that Dev Anand is supposed to be making. Even fans prefer his classics. When an authoritative history of the Hindi film industry is written, Dev Saab will probably be remembered more for patience and persistence than anything else. It requires tremendous confidence to write 436 pages of nothing except oneself. But then, this book is probably his last hurrah. Most of those who purchased the volume in Kathmandu for the author's autograph are probably still keeping it on the coffee table; the volume's design certainly goes well with any décor.

~ CK Lal is a columnist for this magazine and for the Nepali Times.