How Southasia and Oman intertwined

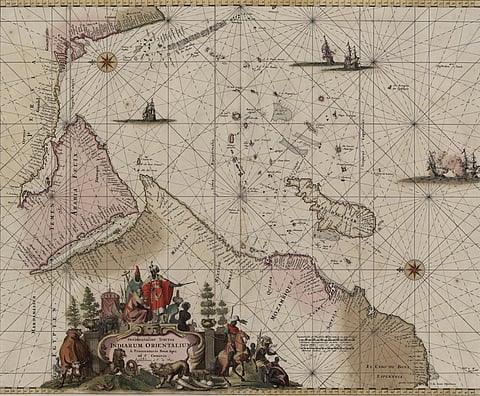

The Southasian samosa has a transnational sibling from which it is said to have been derived: the West Asian sambusak. The sambusak has a similar golden-brown exterior. Once bitten into, its crumbly golden shell gives way to a riot of meaty juices in the centre. This samosa siblinghood is merely one of the numerous ways in which the lives of Southasians and West Asians have been generationally intertwined. Being of and from each other, we see traces of this shared heritage in our modern food habits, music, poetry and even the folk tales we tell our children. This is the parting thought one has upon finishing Seema Alavi's extensively researched Sovereigns of the Sea: Omani Ambition in the Age of Empire. Through the histories of five Omani sultans with varied legacies, the book speaks to the interconnectedness of Southasia, West Asia and East Africa via politics, economics, Anglo-French colonialism, the slave trade and myriad community linkages. Narrating these histories through the lens of the sultans and the Indian Ocean from 1791 to the 1880s, Alavi's book leaves readers pondering over the strict bounds of nation-states, and whether today's borders will ever adequately explain who we are now and whence we came. This book is also an important addition to the growing collection of scholarship on Indian Ocean history.

What makes Sovereigns of the Sea particularly compelling is that it fills historical gaps for those interested in a cohesive story of Oman, Zanzibar and Southasia. Modern Oman also remains synonymous with the sea. I grew up in Oman as one of many "Gulfie" kids of Southasian heritage. As a child flying into Muscat, Oman's capital, I would always request a window seat so I could survey from the aircraft that first view of the city: cerulean blue seas against the dramatic Hajar mountains. Growing up in Muscat, weekend visits to the fish market in Muttrah, next to Port Sultan Qaboos, were a rite of passage, with a pitstop at another bustling market in the same area, the Muttrah Souq. One of my earliest childhood memories from Muscat is the exciting melee of the fish market. My eyes would widen as I watched fishermen and vendors sell wares, building my anticipation for what we would soon eat for lunch. The Muttrah Souq brimmed with all sorts of knickknacks: dates and hookahs of a hundred sizes, silver pouring out of every spare inch of space in the shop rows. As interesting as the wares was the variety of people passing through. Aside from the habitual tourists, resident Southasians and Africans filled the market both as sellers and zealously haggling customers. One could spot Omani men and women in dishdashas and abayas, as well as Southasians in saris and Africans in Kanga-inspired prints. The souq has, of course, changed over the years, but it still possesses much of the same hubbub and soul as it did when I experienced it as a child almost thirty years ago.