Neither here nor there in chhit mahal

On 6 June, Bangladesh and India signed the historic Land Boundary Agreement. Originally conceived in 1974, it was aimed at settling long-standing territorial issues between the two countries. The deal includes swapping 200 enclaves – patches of island territories surrounded on all sides by another nation. The residents now have the right to stay where they are or move. In our March 2014 issue 'Reclaiming Afghanistan', Anuradha Sharma reported from one such enclave, exploring the historical and political stories behind these geographies. Here's an extract from the reportage. To read more, you can purchase the print or digital version of the issue.

The town of Cooch Behar, located in the foothills of the eastern Himalaya some 700 kilometres north of Kolkata, was once the seat of the Koch kings. It is now the headquarters of a district, also called Cooch Behar, which was a princely state during British rule in India. With Maharaja Nripendra Narayan's palace here and the Madan Mohan temple there, the town is dotted with historical buildings and heritage sites and is a popular tourist destination in West Bengal.

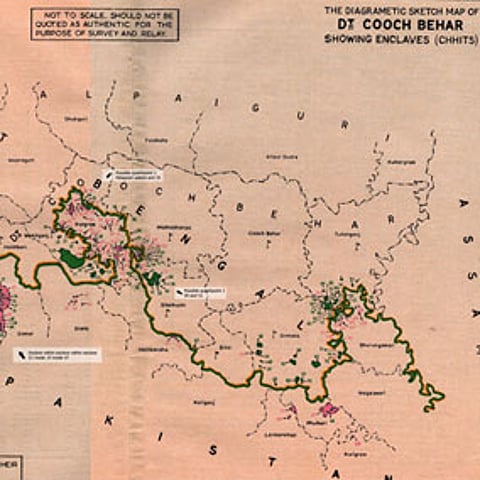

There's a cluster of enclaves in Cooch Behar – Madhya Masaldanga is about an hour-and-a-half's drive from the district headquarters. They are also strewn all over the neighbouring district of Jalpaiguri and the state of Assam. This 'archipelago' of landlocked islands even has 24 (21 Bangladeshi and three Indian) counter-enclaves – i.e. enclaves within enclaves – and also the world's only counter-counter enclave, Dahala Khagrabari. It is an Indian patch of agricultural land, roughly the size of a football field, inside a Bangladeshi enclave, which is within an Indian enclave inside Bangladesh.

How did such a spectacular geography come to exist? A number of theories exist.

The enclaves as they are today are said to have resulted from the treaties between the Kingdom of Cooch Behar and the Mughal Empire in 1711 and 1713, ending long periods of war in which the Mughals wrested control over several districts or chaklas of Cooch Behar. The Mughals were unable to dislodge some of the more powerful Cooch Behar chieftains from their fiefs. When the chaklas were handed over to the Mughals by the treaty of 1713, the patches of land held by loyal Cooch Behar chiefs remained with Cooch Behar, detached and as enclaves.

However, the boundaries are said to have been fragmented and territories interlocked even before that. "The enclaves… probably already existed at a zamindari or chakla level… The 1713 treaty only raised it from this landlord/landholding level to a quasi-international level for the first time," explains Australian anthropologist Brendan R Whyte in 'Waiting for the Esquimo: An historical and documentary study of the Cooch Behar enclaves of India and Bangladesh'.

More popular, however, is a folktale that claims the enclaves were the result of chess or dice games between the Maharaja of Cooch Behar and the Faujdar of Rangpur in which patches of fertile agricultural land were wagered. Another legend has it that a British officer – Cyril Radcliffe, who drew the India-Pakistan border – was either drunk or in such a hurry that he dropped ink-spots on the map.

Whatever be their genesis, the enclaves existed without causing much bother to anyone in undivided India. In 1947, India gained independence and was partitioned: Rangpur went to East Pakistan and Cooch Behar merged with India in 1949.

***

After Partition the Indian and Pakistani enclaves remained more or less forgotten, their status respected by both countries, for a decade or so. But border tensions between India and East Pakistan became more acute in the late 50s with a series of alleged border violations and live-fire exchanges between opposing forces. The controversial 1958 Nehru-Noon agreement between Jawaharlal Nehru of India and Malik Firoz Khan Noon of Pakistan, resolved to exchange the enclaves. The pact also decreed that Berubari in Jalpaiguri district of India would be bifurcated and divided between the two neighbours. It resulted in a spate of protests in India.

Noon's government was soon to be dismissed by Pakistan President Iskander Mirza who declared martial law in the country. Despite the flak that Noon drew following the pact, it was later ratified. Nehru, too, had to face the wrath of the Indian parliament for entering into an agreement with a foreign country without consulting Parliament. India would have had to part with about 28 square miles and 11,000 people in exchange for 17 square miles and 9,000 people, while also losing half of Berubari, a strip of land jutting into the neighbouring country.

There were widespread protests and demonstrations, especially in Berubari where the people opposed the idea of joining East Pakistan. The West Bengal government was vehemently opposed to the ceding of Berubari and took umbrage at the fact that it was not even consulted. At the behest of President Rajendra Prasad, the matter went to the Supreme Court in 1959 and a year later the Apex Court held that the transfer of land could not be possible without an amendment to the Constitution.

The agreement soon fizzled out and was almost forgotten in the context of the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War that separated East Pakistan from West Pakistan.

In 1974, Indira Gandhi and Sheikh Mujibur Rehman signed the historic Land Boundary Agreement that came to be known as the Indira-Mujib treaty. The two countries agreed to exchange the enclaves, except Dahagram and Angarpota, which were to remain with Bangladesh. The enclave dwellers were to have the right to remain where they were. India was to retain Berubari and lease the Teen-Bigha Corridor to Bangladesh in order to connect Dahagram and Angarpota with mainland Bangladesh. Bangladesh amended its Constitution and ratified the agreement the same year. India is yet to do so.

The Teen Bigha Corridor (3.17 acres) was transferred to Bangladesh on 26 June 1992, amid protests by opposition parties in India that met with lathi-charges and live-fire resulting in arson and deaths. The Corridor was open only for an hour initially. The timing was increased to three, six and 12 hours until finally in 2011, it was opened for 24 hours.

In 2011, Indian and Bangladeshi Prime Ministers Manmohan Singh and Sheikh Hasina signed the Protocol to the 1974 Agreement – stipulating the exchange of land in 111 Indian enclaves in Bangladesh and 51 Bangladeshi enclaves on Indian soil – at a summit in Dhaka that once again brought cheer to enclave dwellers who celebrated by distributing sweets.

Almost 40 years since the Indira-Mujib agreement and two years since the Hasina-Singh Protocol, India is still to ratify the accord.

~This article was first published in our quarterly 'Reclaiming Afghanistan' in March 2014. To read more, you can purchase the print or digital version of the issue.

~Anuradha Sharma is a Kolkata-based freelance journalist and writer. She covers politics and culture in Southasia. She tweets at @NuraSharma.