In October 1939, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas penned an open letter to Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, who had commented some years previously on cinema being a "sinful technology". Abbas' letter argued with Gandhi to reconsider the potential of the medium. "My dear Bapu," he wrote, "Today I bring for your scrutiny and approval a new toy my generation has learnt to play with – the CINEMA!…All that I wish to say is that cinema is an art, a medium of expression and therefore it is unfair to condemn it. You are a great soul Bapu… Give this little toy of ours, the Cinema, which is not as useless as it looks, a little of your attention and bless it with a smile of toleration."

The Cinema, as Abbas called it, was just one part of the vast and varied repertoire of his work. Yet it served the same purpose Abbas sought to serve through all his life – of creating social reform, debate and change. In a full life, Abbas wrote over 70 books, directed around 20 films and wrote some of the most iconic screenplays of his era. This prolific communicator and committed man of the masses is a towering presence in the history of Mumbai cinema, with a legacy that is only now being fully recognised. In 2015, a year after his centenary, a volume titled Bread, Beauty, Revolution: Khwaja Ahmad Abbas 1914-1987 was published, which brings together a collection of his writings, interviews and translated work. The glossy volume, edited by Iffat Fatima and Syeda Saiyidain Hameed, draws from a diverse range of sources, and is a useful introduction to his many talents, for a generation that too often knows him as "the man who launched Amitabh Bachchan". The title of the book draws from Abbas' experience at the Andhra Progressive Writers Conference in 1982, held in Madras. As poem after poem was read out in unfamiliar languages, Abbas was struck by the universality of the slogan that followed each session: "Inquilab Zindabad". It was a slogan, he noted, he had heard across the length and breadth of India. He interrogated his companions for a few more words common to different Indian languages and came up with the three used here: bread (ann), beauty (sundar) and revolution (inquilab).

In my earlier column on the magazine Filmindia, I had referred to Abbas' unlikely friendship with the earthy Baburao Patel. Patel had given space to the opinionated and intellectual young critic, and the volume reproduces one of his reviews on the RKO production Gunga Din. Abbas rips into the movie with a fine rage, calling out its racist and patronising overtones. In these times of easy sloganeering, it is a relief to be immersed in Abbas' brand of patriotism that could lead him to take on representations of his country, but also encourage dissent and questioning. In an interview to Indian Literary Review, he said: "I describe myself not as a journalist but as a communicator. I want to communicate my ideas, my impulses, my ideologies, to other people." Writing was his first love, and he was not only prolific but also often wrote stories in one sitting. For instance, a short story was written on a train ride between Aurangabad and Bombay, as the Bread, Beauty, Revolution volume notes.

As a director, Abbas created path-breaking work that failed commercially. One of my favourite texts in the book records the production of Dhartike Lal, Abbas' directorial debut. The film was based on the tragedy of the Bengal famine, and was produced in collaboration with the Indian People's Theatre Association (IPTA). Actors included stalwarts like Balraj Sahni and Murad. Abbas recorded the difficulties in raising finances and shooting on a shoestring budget, all the while being aware of the significance of what was being done. "We were producing a totally different kind of film in India, and so we had to set traditions and precedents," he noted. At the first screening for an audience of about 300 people, when "…the legend 'Peoples Theatre Stars the People' was flashed on the screen, there was spontaneous cheering."

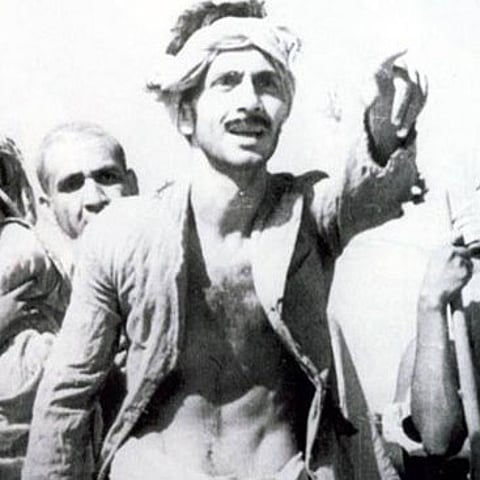

An important thread in the volume is Abbas' collaboration with director Raj Kapoor. In contrast to his own productions, Abbas' presence as a screenwriter on Kapoor's films created cult films that were also huge hits. In a 1986 interview with his co-writer VP Sathe on All India Radio, he revealed that he considered Awara as the most successful of these collaborations, with Shree 420 being "about ten percent less". But as time went by, the joy of this association wore off. "Frankly speaking, I was least happy about Bobby. I will say it is 70 to 80 percent Raj Kapoor. I have no share in this except very little." One of the great attractions of this volume is the inclusion of film stills and posters, besides wonderful photographs (unfortunately unindexed) of Abbas with his illustrious peers and friends. There are also excerpts from letters, including one written from Russia to his brother in 1954, recounting the popularity of Awara, and of Abbas' lifelong idol Jawaharlal Nehru, in the country.

A section of the book is devoted to 'reminiscences', with accounts about Abbas by the likes of Shabana Azmi and Amitabh Bachchan. The latter recalls traveling to Goa with the unit for Saat Hindustani, "by train and 3rd class….It was the best he could afford, but also the best that most Indians could afford. That was the deciding factor." At night, Abbas would write the script for the next day's shoot by the light on a lantern set on the floor.

Clearly, Abbas' work and personal life were deeply intertwined, like so many of his colleagues in IPTA and the Progressive Writers Movement, including Sardar Jafri, Kaifi Azmi, Ismat Chughtai and Zohra Sehgal. His career reflects a certain face of Bombay during the 1940s and 50s, when these talented men and women made their way to the metropolis. Abbas shaped the city not only as a filmmaker and screenwriter but also as a journalist. His weekly column the Last Page appeared for over 40 years in the legendary Rusi Karanjia's tabloid Blitz, and was a fixture for city readers. The column also appeared as Azad Qalam in the Urdu and Hindi editions.

There are many beautiful personal moments in this volume that reveal the complexity and richness of Abbas' inner life. His reminiscences of his wife Mujji, for instance, and how she made herself invaluable to his writing. There is a harrowing anecdote of how he was forced to take part in a hunger strike by his reform-minded father, when he was only a few months old, to protest against the women of the family indulging in wasteful expenditure at a wedding. All night, father and son remained sequestered in a sarai, Abbas "half-dead" with hunger, until the contrite women rushed to the spot in the morning and "swore by the Holy Quran that there would be no extravagance and ostentation in the marriage." There is a delightful photo of Abbas in an apron, busy in the kitchen with vegetables. My favourite section of the book, however, is Abbas' will. In this economically dramatic piece of writing, he decreed that his funeral procession should be accompanied by a Maharashtrian Lezim band, and should pass by the statue of Gandhi at Juhu beach, and then the sea, which he loved. He also asked to be buried with pages of his column as part of his shroud. The book does not tell us if these instructions were fully carried out. I hope so. For a man who spent his life pursuing words, it seems fitting that he was laid to rest with them.

~Taran N Khan is a Mumbai-based journalist who writes on cinema, Islam and gender. She has been traveling to Kabul since 2006 where she worked closely with Afghan media producers and filmmakers. Her work can be seen at www.porterfolio.net/taran.

~This article is part of a series of column on cinema by Taran N Khan for Himal Southasian. Read her earlier column on the documentary Castaway Man.