The life and times of a British journal of Islam

The Westerner is disgusted with his own Church, and wants something reasonable and liveable to substitute for it. Muslim tenets appeal and go to the very heart of every sensible man here.

– The Islamic Review, January 1926

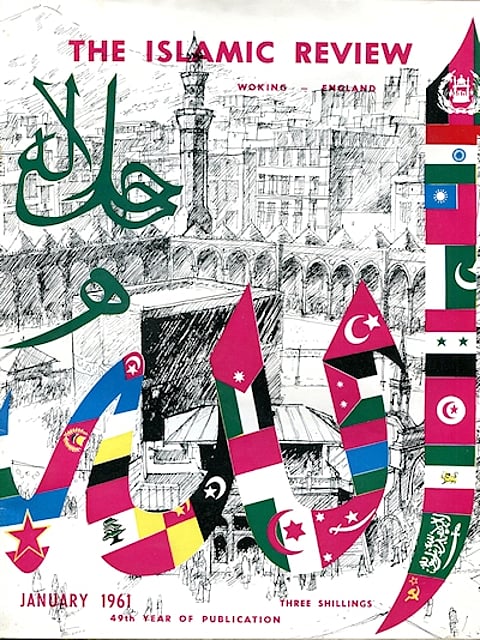

In the autumn of 1912, a Punjabi Muslim lawyer from Lahore arrived in London, having travelled from his hometown with the dual purpose of pleading a civil case in England and establishing a Muslim missionary presence there. Shortly after his arrival, Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din travelled to Woking, a town 40 km southwest of London, and also the site of the first mosque built in Britain, the Shah Jahan Mosque. Built by the British-Hungarian orientalist G W Leitner, with funding from Begum Shah Jahan of Bhopal, the mosque was in a state of disuse and disrepair by then. But Kamal-ud-Din identified it as an ideal centre for the propagation of Islam within Britain and Europe, and established the Woking Muslim Mission, which administered the mosque for the next half century. In less than five months of his arrival in England, Kamal-ud-Din, a Lahori Ahmadi — from a minority school within a minority sect of Islam — had also founded the Islamic Review, which would go on to become one of the most prominent journals of Islamic thought in the West in the 20th century.

Photo: Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha'at Islam Lahore (U.K.)

Emerging from the colonial encounter, especially with Christian proselytisation in the Subcontinent, some theologically minded Muslims, like the members of the Woking Muslim Mission, saw it as their duty to reclaim Islam's position as a 'world religion'. The Review became their most notable mouthpiece. Though rarely made explicit in the journal's articles, the historical worldview it expressed was also linked to the Mission's association with the Lahori branch of the Ahmadiyya movement.

When the Review began publication, the Ahmadiyya movement was less than a quarter century old, having been founded in 1889 by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, a revivalist leader from Qadian, Punjab, in present-day India. Members of the Ahmadiyya community – both its branches, the larger Qadian group and the minority Lahore group – revere Mirza Ghulam Ahmad as the renewer (mujaddid) of Islam, and the promised messiah. The two branches, however, differ on his prophetic status: the Lahori group, with which Kamal-ud-Din was closely associated, argues that his status as the messiah did not mean he was also a prophet. The Qadian group, on the other hand, while believing that the Prophet Muhammad was the last 'law-bearing' prophet, consider Mirza Ghulam Ahmad as a non-law-bearing prophet. Accusations by some that the Ahmadiyya movement is heretical are generally focused on this latter belief. But both groups have been targeted by anti-Ahmadi violence and laws, especially in Pakistan.

The Review archives enable us to examine the centrality of Ahmadi Muslims within the history of Islam in the West in the 20th century. Narratives of the growth of Islam in Western Europe and the Americas often emphasise immigrant experiences in late/post-colonial Europe, the rise of Black Muslim groups in the United States, and the contemporary struggles of Muslims against discriminatory discourses and laws on both sides of the Atlantic. But Ahmadi proselytisation efforts and their role in the growth of Muslim groups in the West during the early and mid-20th century rarely feature in these narratives, even when they are intricately connected.

The Review also demonstrates the cosmopolitanisms of early 20th-century Southasian and British Muslims working in Woking, as they expanded the reach of their publication across Western Europe, the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia and the Americas. Its archives display the political views of a highly mobile, but often overlooked, cadre of Muslim writers as they navigated Southasian involvement in the two World Wars, independence from colonial rule, Partition and its aftermath, and the shifting politics of religion and immigration in the United Kingdom.

Photo: Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha'at Islam Lahore (U.K.)

But how did a sober magazine, published by an organisation founded by a minority sect of Punjabi Muslims based in the United Kingdom, gain such prominence? How did the Islamic Review grow from a niche publication aimed at proselytising the British elite, to a magazine of Muslim affairs with a global readership?

Between Britain and the Subcontinent

Founded in 1913, and cycling through a number of variations of its name in its first decade of existence, the Islamic Review was explicitly meant to propagate the knowledge of Islam and Indian Muslims among the British public. In its early years, it was also important to impress upon readers the successes of missionary and conversion efforts. The January 1916 edition, for instance, opened with announcement that over the past year "about one hundred Britishers—men and women both—have embraced Islam." Among the earliest and most prominent of the Woking Mission's converts was Baron Headley, whose full name was Rowland George Allanson-Winn. Lord Headley formed a close friendship with Kamal-ud-Din and became the Woking Mission's most prominent British advocate. By 1915, the Woking Mission and the Review had become closely linked with Lord Headley's British Muslim Society, an organisation of converts who debated the position of Islam in Britain and Europe, largely amongst themselves. The Review regularly featured updates of their meetings, designed both to communicate the normalcy of Islam to non-Muslim Britons and to display the progress of Woking's missionary activity to Muslims abroad, particularly those in Southasia.

Photo: Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha'at Islam Lahore (U.K.)

Another aim of the Review was to engage with the British academic community. Among the first articles in its first edition was a letter to the editor authored by Edward Granville Browne, a scholar of Persian and religious studies, who advised Kamal-ud-Din that the magazine would not succeed if it remained primarily academic, and that it should aim to be engaging and conversational. Browne's engagement with the magazine is reflective of the personal relationships between immigrant Southasian intellectual and religious elites, and their orientalist counterparts in Britain. The editors and writers at the Review saw the British media and popular discourse as either prejudiced or misinformed about Islam. Their relationship with British academics and orientalists was somewhat different: they vacillated between praising their translation efforts as accurate and useful, and dismissing their understanding of Islam as lacking in complete theological comprehension.

Perhaps because the founder of the Ahmadiyya movement, as well as Kamal-ud-Din himself, had studied and ultimately the rejected Christianity, the Review pursued debates with British Christian missionary ideologies. The journal's early writings placed a strong emphasis on the role of Jesus in Islam, and one recurring section, titled 'Problems for the Evangelist', aimed to poke holes in the proselytising positions of the Christian missionaries. But it also offered these same missionaries a space for debate. The Review also carried frequent comparative pieces, often authored by British converts to Islam, like Hafeena Bexon, looking at moral teachings across Biblical and Quranic scriptures. The journal's close association with the British convert community meant that it had a ready supply of willing authors who claimed extensive knowledge of both Biblical and Quranic discourses.

Even as the Review situated itself within British public discourse, its political milieu remained largely, though never exclusively, Southasian. This became particularly evident after the British Empire's entry into the First World War, when articles in the Review emphasised India's role in the war and began to debate the Subcontinent's postwar political future, including independence. Like many contemporary publications with a Southasian connection, especially those published by Muslims, as the war came to an end, it took up the question of the British Empire's relationship with the Ottoman Empire and the emerging Khilafat movement, a pan-Islamic campaign launched by Muslims of the Subcontinent to pressure the British to restore the Caliphate. Reporting on the meetings of the Indian Khilafat delegation with British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, the Review accused him of misrepresenting the interests of Ottoman subjects by "depriv[ing] the Mussulmans of these regions of their freedom and carry[ing] on aggressive Imperialistic designs under the cover of self-determination." The journal even secured an original article from Khilafat leader Mohammad Ali Jauhar for its April 1920 issue, in which he argued that European Christians could not understand the institution or importance of the Khilafat movement without some grounding in Islamic history and theology.

Photo: Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha'at Islam Lahore (U.K.)

As was the case with many Southasian Muslim journals and papers, the experience of the Khilafat movement made the Review a more explicitly political project. Prior to it, the journal focused primarily on clarifying points of theology and, in the first years of World War I, its political criticisms were largely limited to the occasional protest against the Indian Press Act of 1910 and other forms of colonial press censorship. In the wake of the Khilafat movement, however, the journal turned strongly towards Southasian Muslim politics. Never abandoning its theological bent, in the interwar period, the journal also featured articles arguing that Britain's failure to preserve the Caliphate had perhaps permanently alienated its Indian Muslim subjects. Another, titled 'Growth of Nationalism in Muslim Countries', reprinted from the Calcutta newspaper the Star of India, argued that Muslims could be nationalists without undermining the global unity of Islam. Although this political focus never became the journal's primary emphasis, it reveals close associations between the evolving politics of Muslims in Southasia and the journal's Britain-based editors.

Muslim, Ahmadi, Lahori?

Over the years, as the Review explicated on theology and politics, there was one curious omission from its pages: it rarely made explicit the Ahmadiyya associations of many of its most prominent writers. Some scholars have suggested that Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din was apparently advised not to attempt to convert British Christians to the specific views of the Ahmadis, and instead to stress a vision of Islam that was universal – almost minimalist. As a result, very few of the British converts who worshiped in Woking and contributed to the Review characterised themselves as Ahmadi Muslims.

The Review was founded only a few years after the death of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, and many of the theological differences between the Lahore and Qadian groups were not yet treated as settled by members of either group. Around the same time, Christian writers in the West had started expressing concern about the Ahmadis, with people like the Episcopal minister James Thayer Addison from Massachusetts characterising them as "a recent heretical offshoot of Mohammedanism." Perhaps because the Review was published in English, with missionary aims, it received greater pushback from the Christian critics than their Muslim counterparts. In the January 1929 issue of the Harvard Theological Review, Addison sounded an alarm to concerned American and British Christians about the work of the Ahmadiyya movement and the Woking Muslim community. Depicting the Lahore group as particularly slippery in its tactics of self-representation and conversion, Addison warned Western readers that the group was "actively anti-Christian" and attempted to appeal to the "Western mind" through reason and claims of "progressivism". For Addison, painting the Woking mosque and its publications as schismatic was ultimately way to undermine their legitimacy with potential British converts.

Some non-Ahmadi Muslim intellectuals in British India also decried the Review, for including quotes by Ghulam Ahmad in its pages and for using its press to reprint Ahmadi treatises. However, it was not until the interwar period that other Southasian Muslims began to express vocal opposition to the international work of the Lahori Ahmadiyya. The Southasian critics, however, often distinguished between doctrine and missionary zeal, praising the later while decrying the former. When Lord Headley visited India in 1927, he was widely hailed as the most prominent of the British Muslims, but he also faced questions about his association with the Woking Muslim Mission and especially the Mission's Ahmadi character.

In other words, the Review and the Mission were received ambivalently by Southasian Muslims, who embraced narratives of European conversion but expressed concerns about the individuals who had converted the Europeans, especially Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din. Umar Ryad, a scholar of transnational Islam, has demonstrated that in the interwar period even some Salafi leaders in the Middle East applauded the Woking Mission's conversion efforts and cited the Review as a powerful and positive force for the propagation of Islam in the West.

In the decade following Partition, even as anti-Ahmadi sentiment became increasingly vocal and violent in Pakistan, the Review continued to remain circumspect about sectarianism and included the writings of both Ahmadi and non-Ahmadi Muslim intellectuals. Indeed, many of its references to the persecution of Ahmadis in this period were relatively oblique. For instance, only months after the 1953 anti-Ahmadi riots in Pakistani Punjab, the Review defended the recent declaration of Pakistan as an 'Islamic Republic' against the criticism that the move was "theocratic" and "regressive", and by extension, against concerns that it would embolden anti-Ahmadi and anti-Shia majoritarian impulses. When the Pakistan government declared Ahmadis non-Muslims in 1974, the magazine was no longer around.

Photo: Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha'at Islam Lahore (U.K.)

As the Lahori Ahmadi community expanded, setting up bases not only in Lahore and Woking, but also in the United States, Germany and Indonesia, its international centres became important nodes for the spread of the Islamic Review. This internationalism of the Ahmadiyya movement, and the aim of addressing a wider public, informed the writings of the Review in the mid-20th century, when its focus became more transregional.

A transregional project

After the Second World War, the writers and editors at the Islamic Review increasingly identified with anti-colonial movements across the 'Muslim World', which for them also included areas with large Muslim minorities. But even prior to that, the magazine did not cover events and ideas specific only to Britain and India. In its first two decades, its authors maintained a close focus on Egypt, where, they argued, the declaration of a British protectorate had made greater space for Christian missionary activities, endangering the local practice of Islam. Beginning in 1914, the journal was also periodically, although not consistently, translated into Arabic for circulation in Egypt, other parts of North Africa, and the Arabian Peninsula.

In the late 1940s and 1950s, the Review's commitment to an internationalist discourse deepened and expanded. The January 1951 edition is representative of the Review's engagement with global anti-colonial and anti-imperial movements across the Muslim World. The roster of articles included 'The Struggle of the Tunisian People for Liberation', 'Egypt, Her Demands, the Future of the World Islam', and overview of the status of Muslims living in Afghanistan, Soviet Uzbekistan, Turkey and the United Kingdom. "The world of Islam has just started to take up the thread of its unity," one article explained, "But this unity will never be materialized or complete so long as foreign troops are on any… of its component parts."

While this perspective was certainly not unique to the Review, it broadly reflected the particular cosmopolitanisms of the Southasian and British Muslims behind it. The writers frequently cited their correspondence with Muslim intellectuals in the Arab World, Iran and Southeast Asia, and casually noted their own movement, not only between Lahore and London, Delhi and Woking, but also to Cairo, Damascus and Cape Town. By 1950, each issue featured a note advising readers that they could write to a local agent for subscriptions in cities as far away as Lagos and Basra, San Francisco and Kuala Lumpur, Colombo and Istanbul, Durban and Berlin. Starting with the September 1967 issue, the Review's title was modified to the Islamic Review and Arab Affairs.

American afterlife

With the growth of the non-Ahmadi and non-convert population of Muslim immigrants in Woking and the surrounding areas in the 1960s, the influence of the Woking Muslim Mission declined. Around 1971, the Shah Jahan Mosque went through a change in guard, coming under mainstream Sunni leadership. With that, the Islamic Review, and associated Lahori Ahmadi missionary activity from Woking, ceased. But the journal had a curious afterlife.

Beginning in 1980, a new version of the Islamic Review was published in the United States from the California branch of the Lahori Ahmadiyya. Announcing the foundation of this new Islamic Review, the editors did not claim to be restarting the older magazine so much as paying homage to and honoring the work of the Woking Mission. The new journal was an explicitly Ahmadi publication, featuring in its first year several extracts and commentaries on the writings of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad and articles decrying the persecution of the Ahmadis in Pakistan. Later issues even included an opening coda titled 'Our Beliefs and Aims' that stated the theological and social views of the 'Ahmadiyya Anjuman Ishaat Islam-Lahore', the formal title of the Lahori Ahmadiyya.

At the same time, the Islamic Review of the 1980s retained its predecessor's focus on reaching non-Muslims in the West. In some ways, California may have been an even more natural fit for the magazine than Woking: while the Woking Muslim Mission saw some notable success in converting elite and wealthy Britons to Islam, Ahmadiyya groups were more successful among African American communities in the United States. Whereas the Woking group had articulated Islam as a progressive and modernising religious ideology to educated, liberal residents of the late-imperial Britain, in the US the new magazine emphasised social justice and racial equality.

More than a decade before the foundation of the Nation of Islam, and nearly thirty years before Malcolm X led a relatively large-scale embrace of Islam among some African American communities, members of the Ahmadiyya preached Islam as a system of racial justice in the United States. Indeed, some scholars have argued that Wallace Fard Muhammad, the founder of the Nation of Islam, was shaped in his beliefs by his interactions with Lahori Ahmadi missionaries.

The second iteration of the Islamic Review lasted for less than a decade; it was discontinued in 1989. In 1991, the Lahore Ahmadiyya movement in Ohio restarted the Review, combining it with a discontinued magazine from Lahore titled The Light – which was forced to cease publication in Lahore due to anti-Ahmadi censorship – reflecting the long tradition of cross-continental collaboration that characterised the Review's history. The Light and Islamic Review continues publication to the present day.

Forgotten histories

From its early years under Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din and its association with British converts to Islam, to its reincorporation in 1980s California, the Islamic Review's cosmopolitanism thrived on challenging expectations: it was an internationalist magazine that embraced nationalist movements across the Muslim World. It was a publication founded and led by Southasians that has been most remembered for its association with elite Britons. It was run by leaders of a minority group within a minority sect of Islam, but rarely made that fact explicit and instead focused on universal appeal for most of its history. It was aimed at convincing the non-Muslim British public of justice and progressiveness inherent in Islam, but found audiences across the colonised world.

With its complexities and contradictions, the Islamic Review paints a picture of a rich and vigorous Muslim intellectual life in Western Europe in the early and mid-20th century. Indeed, the magazine's longevity and its resistance to easy categorisation seem related. Like many of its founders, editors, and writers, the Review showed a remarkable ability to adapt itself across geographies and regions, speaking to diverse audiences about what it saw as the universality of Islam.