How Urdu travel writers brought the world back home

When once asked about his favourite childhood reads, the renowned Urdu writer Naiyer Masud mentioned Khaufnak Dunya: Jazira-i Borniyo meñ Safar aur Jangaloñ meñ Shikar, an exhilarating account of hunting expeditions in the "terrifying" jungles of Borneo. Published in 1908 and written by a Punjabi dentist named Sayyed Muhammed Ali Shah Sabzvari, it was part of a trilogy featuring his adventures in Borneo, Kenya and New York. Masud did not recall Khaufnak Dunya for its delicate prose or eloquent turns of phrase, but for the joy of reading a dramatic travel account akin to Robinson Crusoe or Gulliver's Travels where the protagonist happened to be an Indian man. Sabzvari saw and presented Africa and Southeast Asia for his Urdu readers as sites of play and pleasure. He imagined himself as living a classic colonial fantasy – swindling gullible locals, setting up base in exclusive enclaves where he could relish his favourite food and music, and enjoying salacious pursuits with foreign women. Read today, these stories do not offer new insights for rethinking geographies or champion anticolonial action. Instead, they reflect Southasia's contentious and layered global past.

The rapid expansion of steamship and railway networks in the 19th century offered Southasian travellers the possibility of exploring new worlds with relative ease. Voyagers encountered plurality and difference, which helped widen their horizons in some ways while reifying their own sense of identity and belonging in others. The ability to challenge physical borders and explore new geographies and peoples, however, also sometimes strengthened views of social hierarchies and otherness. Travel did not only build cosmopolitan views of the world, it also brought forth dissonance and friction. Daniel Majchrowicz's The World in Words: Travel Writing and the Global Imagination in Muslim South Asia explores everyday voices in Urdu to trace the region's uneven relationship with a rapidly interconnected world. It illustrates the ways in which Southasians imagined new geographies and cultures and their relationship to them, conveyed through the production and circulation of travel writing across the subcontinent from 1840 to 1990. The book unearths the story of how the travelogue, or safarnama, became a popular genre for Southasian readers' everyday consumption, alongside new literary forms like the novel and the magazine.

Majchrowicz describes The World in Words as located between the fields of history and literature, telling the story of the circulation of ideas in the Subcontinent. The monograph zooms in on travelogues as a "literature of aspiration", whereby voyagers could convey their visions of what the world is and what it ought to be to curious readers back home. The writers of these travelogues were mostly not the political elite or colonial administrators but rather small-town Muslim and Hindu writers – men and women – who did not consider their position as colonised subjects to be a deterrence in engaging with the broader world physically and intellectually. The World in Words' major contribution is that, unlike much earlier scholarship on imperial travels, it does not pin Europe as the centre of wonder and progress, but turns towards journeys in Asia and Africa as a way of bringing forward the full potential of world-making in Urdu. The result is a refreshing view of the pathways leading to Southasia's global past, unburdened by the urge to write back to Empire.

The seduction of travel was wide-ranging. These writers travelled for pleasure, pilgrimage, education, worldly success and even nostalgia. Majchrowicz deftly avoids submitting these travel accounts to the hegemony of a singular intellectual orientation – cosmopolitanism, universalism or even Muslim exceptionalism. A vast corpus of existing texts have focused on how colonised subjects experienced Europe and its impact on their articulations of progress, homeland and nationalism. Others have chosen to prioritise what the literary scholar Isabel Hofmeyr calls narratives of "third-worldist subalterns at sea", ones that uncritically celebrate positive responses to ethnic, religious and cultural pluralism within the Global South. Southasian voyagers often carried forward worldviews and civilisational markers rooted in biases, prejudices and narratives of superiority. Majchrowicz's caution against these narrow ideological frameworks finds echo in the historian Nile Green's article 'Waves of Heterotopia', which alerts readers to view vernacular travelogues from the Indian Ocean as repositories of multilateral sets of responses to writers' encounters with geographical and cultural difference. Anti-colonial resistance, transnational activism and South-South solidarity were prominent outcomes of travel, but not the only ones. Southasian travellers often submitted to the logics of colonial capitalism and sought wealth and civilisational superiority. Far from forging solidarity, their accounts were often pervaded by racialised perceptions of Asian and African others.

Princes and the Partitioned

The World in Words features a range of Urdu travelogues clustered around courtly, colonial, reformist, pedagogical, religious and postcolonial contexts. It shows, for instance, how rulers of erstwhile Indian kingdoms used travel writing to reinforce their power. The Marathi-speaking Hindu ruler Bhawani Singh's Safarnama Shri Badri Narayan-ji Maharaj Ka (1900) highlighted the positive moral impact of his pilgrimage to Badrinath – which, in turn, further underscored his authority to govern. Both Bagh-i Naubahar (1851) composed at the court of Maharaja Tukoji Holkar of Indore and Sair al-Muhtasham (1852) by Nawab Ghaus Muhammad Khan of Jaora recorded the "enduring glory of their rule" and sought symbolic legitimacy for them amid shifting political claims in British India. These princes saw travel and travel-writing as an investment – a "means to victory" by which they could bring home the fruits of European civilisation and curry support among British readers who otherwise saw them as prodigal despots. Majchrowicz highlights the proliferation of Urdu travelogues even among the remote courts of central India as testimony to the rapid growth of the language's popularity across regions and religious groups at a time when courtly literature was produced primarily in Persian.

A century later, the most significant travel writings were cross-border accounts from the newly created India and Pakistan. These were a means of resolving, or at least attempting to resolve, the enduring trauma of Partition. The journey across the India–Pakistan border was described as ziyarat, which is a visit to a sacred shrine, or a hijrat, which connotes religious migration. Accounts like Ram Lal's Zard Patton ki Bahar (1982) and Abd-al Majid Daryabadi's Dhai Hafte Pakistan Mein (1952) present an "eerie palimpsest" of memories of past homelands and the postcolonial present. By including these writings, The World in Words shifts from "going abroad" to "coming home", with a recognition of travel as a means to reconciliation.

The book delves extensively into the pedagogical roots of travel writing, showing how "travel for knowledge" became an important component of liberal education under British rule. Several low-ranking colonial administrators wrote and published travelogues that served as geography textbooks in colonial North India. Prominent among them was Munshi Amin Chand's Safarnama (1851), whose narrative supported British claims of enlightened rule. The text undermined the presence of Indian princely states and lent an unprecedented territorial unity to India: here, a reader in Punjab could see Orissa as "apna mulk", or her own country. At the same time, the inclusion of Hindu temples and pilgrimage sites prefigured Bengali travel writing's "Hindu inflected nationalism", which sanctified India as a holy Hindu land.

Translation was a key feature of the colonial education project, and the Department of Public Instruction regularly drafted and translated didactic travelogues. The Urdu version of the Scottish explorer Mungo Park's Travels to the Interior of Africa (1842) was among the first accounts to be republished as a textbook and prescribed in colonial Indian schools. Some Urdu travelogues, like the Muslim educationist Samiullah Khan's Safarnama (1880), were translated into Tamil, Telugu and other languages by colonial associations like the Madras School Book and Vernacular Literature Society. Travel by the average Indian was not simply part of the zeitgeist but rather consciously sponsored and patronised by the colonial government in India. Colonial governments popularised travel writing, alongside pedagogical Urdu novels, to foster a scientific temperament and "moral rectitude" among the natives, who they thought were too backward to care about the world.

By the late 19th century, Urdu readers had developed a voracious appetite for travelogues, which could easily be translated into mass sales and profits. Commercial publishers like the Naval Kishore Press inundated the market with accounts of "global exploits" that were not produced with government support or control and could directly address a broader readership. Writers often blurred the boundaries between fact and fiction, adding wordplay and cyclical plots adopted from the pre-existing dastan tradition of epic romances. One of the most widely read travelogues, Munshi Sayyid Ghulam Haidar's Sair-i Maqbul (1872), was in fact a fictional travel memoir of a 17th-century trader, Agha Maqbul Isfahani. Isfahani, who Majchrowicz calls a "Muslim Forrest Gump", had managed to witness all the major events of the time. Maqbul echoed the language of Persian ethical literature and urged his readers to appreciate the fruits of civilisation, study hard and abhor injustice.

Not all popular Urdu travelogues were informative or didactic. Several, like Manzur Ali's versified Safaranama-i Manzur (1894), embraced the "bohemian" possibilities of travel. Manzur journeyed through eastern India and Southeast Asia, evaluating sites based on the beauty (or the lack thereof) of the women he encountered. In Assam, he prided himself as a culturally superior visitor rightfully revulsed at the "charmless" local women, whose sexual availability only smeared the region further in his eyes. Journeys to the "sexualised" East allowed Urdu travel writers to assert their masculine domination over people whom they deemed culturally inferior. There are many such examples in The World in Words that show how the responses of Urdu writers from Southasia to encounters with diversity and difference could often be paternalistic, nativist and even downright racist. However, the book sketches the evolution of this writing, following the arc of apparently insular Southasians being pervaded with a sense of global belonging.

Through women's eyes

Among the most interesting travel accounts from this period, featured in The World in Words, are the travel accounts by, for and of women. Begum Sarbuland Jang's Dunya Aurat ki Nazar Mein (1936) and Fatima Begum's Hajj-i Baitullah (1959) depict the tensions between Islam as an idiom of transregional unity and Muslim women's actual, lived experiences of cultural dissonance. Begum Sarbuland Jang, for instance, was shocked at the sight of naked women in Damascene public bathhouses and the tattooed faces of some Egyptian Muslims who reminded her of oppressed-caste Hindu women at home. Fatima Begum came down harshly on the veiling of Uyghur women, who covered their heads and faces but left their chests shamefully open for all to see. Rahil Begum, in her Zad-i Sabil (1929), remarked at Bahraini Arabs' hatred for Hindustanis and the ill-treatment of Indian passengers by their ship's "Chinese"-looking Muslim stewards. According to Majchrowicz, pan-Islamic ideals could not erase Muslim authors' struggles with racial and class hierarchies, which essentially placed large swathes of Asian and African Muslim women outside the boundaries of Islamic sisterhood.

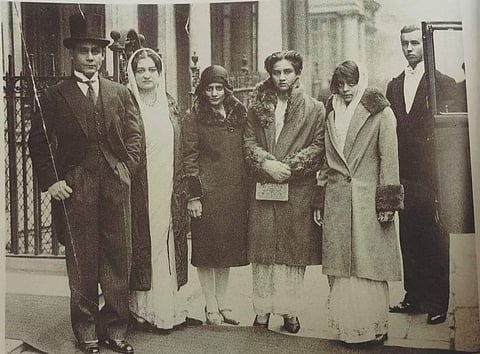

Majchrowicz has been involved with major translation projects including Accessing Muslim Lives, an online archive of autobiographical and travel writing, which he has translated alongside the historians Siobhan Lambert-Hurley and Sunil Sharma. The website is an extensive and unique record of original accounts in over nine languages and contains translated excerpts from a mélange of Muslim voices including bureaucrats, actors, writers, saints and socio-religious reformers. The archive is a corrective measure against approaches in global history that do not consider Muslim autobiographical and travel writing as part of the process of fashioning the modern self. The project's special focus on gendered experiences of travel culminated in the 2022 anthology, Three Centuries of Travel Writing by Muslim Women. The anthology, which spans the 17th and 20th centuries, undoes Orientalist clichés of "veiled" and "walled" Muslim women and foregrounds their participation in a culture of mobility. Muslim women travelled the world as pilgrims, activists, students and even wives and daughters chaperoned by male guardians. Even though not all their travel accounts were meant for public consumption, writing about their journeys abroad afforded Muslim women greater participation in the public sphere. Three Centuries of Travel Writing features translations of magazine articles, book excerpts, speeches and poems to unsettle our assumptions of what constitutes a travelogue and who gets to be labelled a true traveller. The anthology is a crucial step towards writing Muslim women back into the history of travel and showing how travel helped shape their public-facing selves for readers back home.

The book's four broad and overlapping themes are travel as pilgrimage, travel as emancipation and politicisation, travel as education and travel as obligation and pleasure. The collected texts shed light on Muslim women's varied experiences of social, cultural and intellectual transformation. Each section of the book features autobiographical accounts wherein authors constructed and performed a "public image" contingent on their social positioning, individual circumstances and audience. Ummat al-Ghani Nur al-Nisa's journal of Hajj had an intimate tone and was meant to circulate only among family members. The Turkish feminist intellectual Halide Edib's travel account took up the question of women's emancipation and was meant for the widest possible audience. Others, like the Mughal princess Jahanara, wished to express the beauty of nature to all discerning readers, in this case as experienced on her journey to Kashmir.

The power of print

The World in Words captures key moments in the development of Urdu print culture and literary modernity. The popularity of travel writing owed much to increased literacy rates and the advent of cheap lithograph technology in Southasia. The colonial regime saw the promotion of travel as part of their civilising mission, a form of "useful knowledge" which would produce rational subjects. However, as leisure reading became an increasingly popular pastime, the demand for travel literature reached a point where it had to be mass produced, beyond the confines of colonial patronage. The resulting relative independence of the commercial press meant non-elite Urdu readers could impose their own demands and tastes on the genre. Voyagers, in response, provided their audience with both information and entertainment. Even the language of the travelogue was reshaped to mimic dialogues and literary elements from the dastan, or epic romance, to present a combination of fascination and credulity. Majchrowicz calls this the "edutainment matrix", which became a cause of much anxiety among colonial officials and Indian elites who preferred a more scholarly tone for Urdu readers, whom they considered impressionable.

The travelogue was not bound by a singular English or Persian model, but proliferated in a range of forms – as poetry (marsiya, masnavi, rubai), as epistle (khatt-o khutut), as guidebook (rah-numa) and as Hajj accounts (Hajjnama). By the turn of the 20th century, travellers had begun publishing their diary entries and semi-public letters serialised in women's journals and or in private family newspapers. The literary historian Francesca Orsini's Print and Pleasure credits this hybridity with producing a reading public comfortable with a "heterogeneous linguistic and aesthetic repertoire." The World in Words is as much a story of travel as it is of the enthusiastic acceptance of print and independent publishing in a society dominated by oral traditions, narrative and performative techniques and manuscript culture.

Majchrowicz's insistence that Urdu travel writing was produced in a "Muslim" Southasia requires greater evaluation. Muslim voyagers did lionise Urdu travel accounts as a way of fulfilling the Islamic quest for knowledge. However, these proclamations did not hinder non-Muslims from participating in the same literary sphere, nor did it force them to shed their distinct religious character. Throughout the 19th century, Urdu's position as the language of respectability, urbanity and public discourse strengthened. Hindu and Jain writers, mostly men, accepted it as a lingua franca. The World in Words includes several Hindu travel writers, such as Raja Bhavani of Khilchipur, Maharaja Tukoji Holkar, Pandit Kanhaiyalal, Lala Tulsi Ram and Ram La'l. Majchrowicz does not comment on the inclusive "Islamicate" identity of Urdu in this work.

A prominent feature of The World in Words is that it includes translated excerpts from travelogues at the beginning of each chapter to emphasise the importance of making vernacular writing accessible in English. The book's format makes it easier for readers unfamiliar with Urdu to grasp the flavours and range of expression that characterised the writing featured. The translations are a brilliant way to convey how these travel stories were originally meant to be received – as didactic, emotive, fascinating or amusing. Moreover, they open The World in Words up to a broader audience that is interested in global history and world literature from a non-Western perspective but lacks access to vernacular sources. The meaty archive of Accessing Muslim Lives offers new opportunities to construct trajectories of globalisation and modernity as witnessed from the Global South.