The incomplete histories of women migrant caregivers under the British Empire

AMONG THE CHAOS of figures that jostle for space in the British artist George Earl’s 1893 painting Going North is a brown woman tending to a white child as two white men and a white woman – presumably a British family – look on. The scene unfolds in London’s bustling King’s Cross railway station, and the painter’s portrayal of the brown woman suggests she may be from India or elsewhere in Southasia. In the Victorian watercolourist Helen Allingham’s 1877 On Dover Beach, a female figure who could also be read as Southasian supervises three white children – clearly her wards – playing among shallow waves. The creation of both paintings in the late 19th century coincides with the height of British imperialism, when colonial families in India were known to depend on colonised subjects for childcare and other domestic services. It’s not hard to imagine, then, given the decidedly British settings of Earl and Allingham’s paintings, that some of these “native” caregivers travelled with their British employers along the circuits of Empire into the very heart of the metropole.

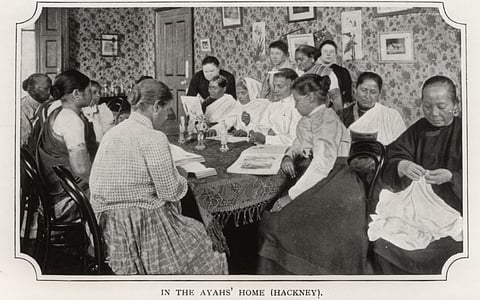

Adding heft to this assumption are descriptions of these paintings in ‘Ayahs and Amahs: Transcolonial Journeys’, a recent project studying female care workers from India and China who journeyed back and forth with colonial families between the United Kingdom, Australia and Asia. The project’s curators describe Allingham’s On Dover Beach as “a nostalgic portrayal of the world of working women” that “displays the British empire’s dependence on the carework of women of color.” The text accompanying Earl’s Going North describes colonial careworkers as “an integral part of British social fabric in the late nineteenth-century,” and King’s Cross station as “a major public transport hub, taking ayahs who arrived from India north to employers’ homes in Scotland.”