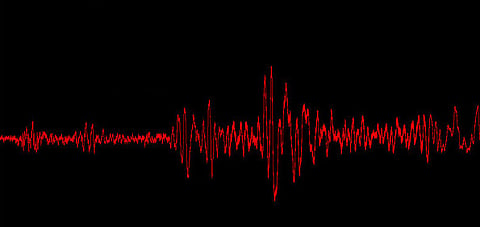

It took just ten seconds to move Kathmandu five feet to the south with its people, houses, temples, trucks and trees. Ten thousand square kilometres of Nepal's mountains, rivers and agricultural land followed suit. The birds were the first to know of this great tectonic shift; they took to the air within seconds of the arrival of the earthquake waves. Then the weakest buildings began to crumble, tanks and pools sloshed water over their banks, and people lurched unsteadily. What the earthquake on 25 April 2015, and a months-long sequence of aftershocks, left behind is tragic and all too well known – a death toll exceeding 8500, an unimaginable disorder of damaged and destroyed buildings, over 3.5 million people homeless, and a 1000 severed tracks and paths in the mountains impeding the delivery of urgent relief supplies.

Two decades ago, for a Himal issue in 1994, this writer described the potential effects of 'the next great earthquake' to hit Kathmandu. In many ways, the April earthquake fulfilled those predictions. But the bad news is that it was not the anticipated 'big one'; a large future earthquake lurks in western Nepal. The good news, however, is that lessons learned from this earthquake could reduce both the economic consequences and loss of life in the next one.