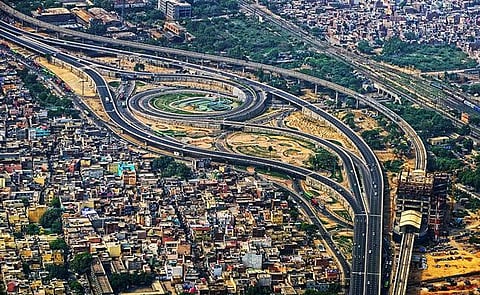

A stretch of the Delhi-Faridabad Skyway

flickr / code_martial

Politics

Where will we live?

Arif Hasan speaks on the 'World-Class City' concept, and its repercussions on urban planning for Asian cities.

A stretch of the Delhi-Faridabad Skyway

flickr / code_martial

flickr / code_martial

The welfare-state model in Europe was born out of an uneasy reconciliation between capitalism and its opponents. Its principles were adopted by most of the newly independent countries in the post-Second World War period. The ethos of the model survived because of the division of the world into socialist and capitalist entities, and because of the presence of a revolutionary China and a militarily powerful Soviet Union on the UN Security Council. In these circumstances, a global market economy was simply not possible. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the repercussions of the failure of the Cultural Revolution in China changed all this, and in political terms capitalism came to dominate the world.

Three important global organisations – the UN, the World Bank and the WTO – along with Western academia, have promoted what has come to be known as the 'free market' economy. The structural adjustment process, which most poorer countries had to undergo in 1990s, facilitated this concept and process. The resulting national economic crunches meant that the poorer countries could not invest in – or, in many cases, even subsidise – infrastructure projects. Instead, these had to be built by the international or respective national corporate sector through international tendering at more than twice the normal cost through the Build-Operate-Transfer and the Build-Operate-Own processes. With such high costs, the poorer sections of these countries' populations have had to depend increasingly on a substandard informal sector for social and physical infrastructure provision.

New concepts have been developed to support the market economy. Some examples: 'it is not the business of the state to do business'; 'cities are the engines of growth'; 'direct foreign investment' (DFI); and the concept of linking economic well being with GDP growth. To promote DFI, the decentralisation of governance systems has also been pushed forward. Increasingly, this is being used to access DFI and identify projects in a non-transparent manner, independent of provincial or central governments.

Political reforms and deregulations pushed through by international financial institutions have also had a major impact on property markets, giving developers and financers (many with links to the 'underworld') a dominant role in the politics of land, and hence in urban politics. The state, in almost all cases, has responded to the demands of this powerful lobby and made land available to it through mostly illegal land-use conversions, new development schemes (often in ecologically inappropriate locations), the bulldozing of informal settlements, and the forceful purchase of formal ones. NGOs and community-based organisations that have challenged this process have faced two constraints: one, an unsympathetic national and international media; and two, an absence of laws to prevent environmentally and socially inappropriate land conversions.

Arif Hasan

Karachi, Bombay, Ho Chi Minh City, Seoul, Delhi – all aspire to become 'World-Class Cities'. According to the World-Class City agenda, the city should have iconic architecture by which it can be recognised. It should be branded for a particular cultural, industrial, or other produce or happening. It should be an international event city (Olympics, sports fairs, etc). It should have high-rise apartments as opposed to upgraded settlements and low-rise neighbourhoods. It should cater to tourism (often at the expense of local commerce). It should have malls as opposed to traditional markets. For solving its increasing traffic problems (the result of a nexus between the automobile, banking and oil sectors) it should build flyovers, underpasses and expressways, rather than restrict the production and purchase of automobiles and manage traffic better. Doing all this is an expensive agenda. For it, the city has to seek DFI and the support of international financial institutions. To access DFI, investment-friendly infrastructure has to be developed, and the image of the World Class city established. For establishing this image, poverty is pushed out of the city to the periphery, and already poor-unfriendly byelaws are made even more unfriendly by permitting environmentally and socially unfriendly land-use conversions. The most important repercussions of this agenda are that the requirements of global capital – and not local requirements – increasingly determine the physical and social form of the city. Projects have replaced planning, and land-use is now determined on the basis of land value alone.

The urban crisis we face today is serious, and it is promoting social and class inequity, ecological damage and environmental degradation, crime and conflict, the displacement of entire communities, the loss of multi-class public space, and the over-consumption of resources. The World Class City concept is, to a great extent, responsible for this damage. Also, its concepts have now taken root in both academia and bureaucracy, and so our future planners will continue to promote these concepts.

With the death of the modernist paradigm, we require a new vision for the development of an 'inclusive' city which can replace the neo-liberal one. We can begin by articulating the principles on the basis of which projects, in the absence of planning, should be designed; the changes that are required in university curricula to make this happen; and the laws and processes that can make citizens the decision-makers in the planning and implementation processes.

~This is a synopsis of a lecture delivered in Kathmandu on 12 October 2012 as part of the Himal/ASD (Alliance for Social Dialogue) Southasia Lecture Series. Click here to download the lecture.

~ Arif Hasan is an award-winning architect, urban planner, social researcher, teacher and writer. He has been involved with the Orangi Pilot Project since its inception in 1982, and has been founding Chairman of the Urban Resource Centre, Karachi, since 1989.