One of the peculiar debates that dominates Indian public discourse is about tolerance. Are Indians tolerant? Or intolerant? Are they tolerant because they are nice? Or do they have karmic indifference about what happens? And is tolerance a good virtue? Is it good to tolerate the bad? Or should we be intolerant of the bad? And how dare someone call us intolerant, aren't we tolerant?

Semantics apart, there is a deeper narrative, soaked in the nation's insecurity and existential angst, as it turns 70 and reaches a point where the old appears to be disappearing fast, and what is new and emergent makes many deeply uncomfortable. At one level it is a comment on the Indian National Congress' decline and the Bharatiya Janata Party's (BJP) rise: the Congress is now reduced to double-digits in the 545 seat Lok Sabha, and the BJP, despite having won only 31 percent of the popular vote has, given the oddities of the first-past-the-post system – and a deeply fragmented opposition – secured a massive majority of seats not enjoyed by a party since 1984. But beyond that, it is also a clash about that much-debated phrase, the idea of India: is it secular or Hindu? Multi-everything or unitary? And do the minorities in the country live in India by right or is that a privilege granted to them?

| FACT AND FICTION Articles on Freedom of Expression |

| This article is from our final issue 'Fact and Fiction'. The quarterly issue has articles on freedom of expression and collection of fiction from the Southasia. Other articles on freedom of expression include: The business of news – Sukumar Muralidharan Freeing the fourth state – Tisaranee Gunasekara Whose media is it anyway? – Neha Dixit The state of surveillance – Sana Saleem Web of Control – Sarah Eleazar Chronicle of a death not foretold – Aunohita Mojumdar |

When some Indians bristle when they are told that intolerance is rising, that bristling is partly because of the assumption that tolerance is a desirable virtue. But the inordinate response from the supporters of the BJP when told that intolerance is on the rise, also shows a deep-rooted insecurity: as if they know that their critics are right, but they want to stifle any conversation about it. They support the government, and confuse the 31 percent mandate with consensus. Anyone deviating from that point is therefore an anti-national. They don't want dissent because dissent implies that there are alternative views and if the entire nation is meant to march in one direction, how can dissenting views be tolerated? So runs that circular argument.

During a conversation with a Gujarati intellectual in January 2016, he asked me with great rhetorical flourish: "Can you say 'we will break our country into pieces' in Pakistan?" I asked him why his yardstick to judge India was a far more flawed democracy which functioned at the mercy of clerics and generals, who often rudely interrupted weak democratic administrations with coups. Do you have such low expectations? Why?, I asked. So he said, all right, forget Pakistan; can you say that in America? And I said yes, you could, and even burn the flag, and the Constitution and the Supreme Court would protect you.

He looked stunned. "Hain? Really?" he asked. That faux-certainty about the world reinforces that aphorism, that a little knowledge is a dangerous thing.

In an argumentative society like India's, dissent flows through its veins. At least in independent India, voters who may have tolerated corruption and bad administration have risen to throw out governments that seek to silence them. At least that was the lesson I learned as a schoolboy in 1977, when Indians voted out Indira Gandhi who had declared internal emergency in 1975, and called for elections 19 months later, confident that she would win.

If the Emergency showed that India couldn't take its democratic institutions for granted, the massacre of Sikhs after the assassination of Indira Gandhi showed the state being complicit in mass murder. The destruction of the Babri Masjid in 1992 showed that politicians from mainstream parties would do little to restrain their followers from taking the law in their hands. And the Gujarat riots of 2002 made it acceptable – even fashionable – to make statements about minorities that were deeply prejudiced, and bigoted.

At each juncture, the so-called silent majority should have risen to stop the madness. Of course many honourable Indians did – the People's Union for Civil Liberties and the People's Union for Democratic Rights published a chilling report on the 1984 massacre called, 'Who Are The Guilty?', which named names and shamed the Congress, and human-rights groups continue to press for justice over the riots in Gujarat and elsewhere. But the vast majority expressed no revulsion; it made mass violence acceptable, because the response was indifference.

The wider spread of and access to the internet, and the ease with which hateful remarks and videos could be shared and amplified, while granting the disseminating party anonymity, emboldened the bigots, as did the indifference of the silent majority. If people think that the biggest issue raised by the killing of Mohammed Akhlaq was not that he was killed, but to ascertain if the meat his family may have been eating was beef or not, then the bigots have succeeded in changing the nature of the debate. Likewise, if people thought that it was all right for vigilantes to stop a van in which cattle were being transported, and assume that the cows were going to get sold to an abattoir, and therefore beat up the men driving the vehicle, then surely the vigilantes couldn't be wrong. The mob raised its ugly face; the state stayed silent, tacitly encouraging it; the people didn't react – and that encouraged the mob further.

In a fascinating essay published in 1995 called 'Ur-Fascism', – Eternal Fascism –Umberto Eco had pointed out that fascism was not sui generis; it didn't emerge out of a vacuum in the 1940s and didn't die with the collapse of Mussolini's regime and the Nazis' Third Reich. He ended the essay by pointing out a series of steps that show how easy it was for fascism to take root in societies. The first of which is to venerate tradition and turn it into a cult. It means building the idea of a society based on a glorified, mythical past when things were supposedly far better than today.

Such worship of tradition also implied the second step – of rejecting modernism. Liberalism, acceptance of other viewpoints, creating a space where diverse communities live, are all ideas that wrestle against a pure, pristine past. Rejection of modernism also meant rejection of progressive thought that aimed to improve society. Eco was writing about the rejection of 1789 and the French Revolution; in contemporary India it could be seen as rejecting the liberal political thought of India's constitution.

Reflecting too deeply about the consequences of an action limits action, the thinking went. And so the third stage – action for action's sake. In such a viewpoint, "Thinking is a form of emasculation," Eco wrote. "When I hear talk of culture, I reach for my gun," the Nazi leader Herman Goering said. When Indian writers complained of intolerance, the Indian minister of culture said, if you are upset, don't write. Writers are thinkers, and thinking too much interferes with action, so he seemed to think. Act, don't ponder, Krishna had told a weak-willed Arjuna, after all.

That led to the fourth stage of Eco's argument – science is rational, and it seeks truth through debate, by listening to different points of view, and such debates are a sign of modernism. When former Reserve Bank of India Governor Raghuram Rajan said that India's tradition of debate and an open spirit of inquiry are critical for economic progress, he was seeking tolerance for alternative views and interpretation. Science thrives on disagreement; and disagreement is treason for Ur-Fascism, as Eco defined generic forms of Fascism.

What Ur-Fascists want is consensus "by exploiting and exacerbating the natural fear of difference." Which brings us to the next point – disagreement is a sign of diversity. Anyone who is different – worshipping a different god, speaking a different tongue, belonging to another culture, eating different food, is a foreigner, an outsider, to be suspected, and not to be trusted. Accept your ancestors were us, and then you are us; otherwise you are them.

Eco said, Ur-Fascism succeeds in a society which is restless, and which has a culture of resentment because some are progressing more than others. And those who don't succeed think that their lack of success is because the game is rigged. Fascism flourishes in an environment of individual and collective frustration. When Slobodan Milosevic told Serbs, "No one will dare to beat you again," he stoked primal impulses, and within two years, the Balkans plunged into horrendous conflict. National pride, national glory, chest-thumping patriotism, narrow nationalism can all be dangerous. Rabindranath Tagore understood this quite well and decried the notion of nationalism in his essays and two novels – Gora and Ghare Baire.

And indeed, Eco's seventh point is the growth of nationalism, which builds the idea of identity around the privilege of being born in the country. That also explains Donald Trump's cynically manipulative and bizarre obsession – one he recently renounced – of trying to prove that Barack Obama was born in Kenya. Pure nationalism is in danger from those who are internationalists, who question patriotism, who talk of clichés like "unity in diversity". For the bigots and nationalists, diversity is a problem, a disease.

And therefore, regardless of facts, the "outsiders" were seen as having more privileges, with myths (that reservations for Dalits are no longer necessary because Dalits have 'everything'), and apocalyptic prognosis based on improbable maths (that Muslims will overtake Hindus by this or that year, transforming the nature of Indian society) shaping ideas and strengthening resolve.

Several other points of Eco's 14-point characteristics of Fascism are pertinent in understanding the current situation. Pacifism, Eco wrote, strengthens the enemy, so anyone speaking of pacifism is a traitor. Indian civil-society leaders and intellectuals who press for closer, better ties with Pakistan are routinely ridiculed. So when the late U R Ananthamurthy became increasingly vocal in criticising Narendra Modi's rise, Modi's followers virulently attacked him, suggesting he move to Pakistan. A BJP leader said those who were critical of Modi should go to Pakistan, and the defence minister Manohar Parrikar said going to Pakistan was like going to hell. That Modi himself made a carefully-staged "impromptu" visit to Pakistan which meant that his leader had gone to hell was a complexity the IIT-educated Parrikar seemed incapable of grasping. And sure enough, when Divya Spandana, or Ramya as the Kannada actor is better known, said Pakistan was not hell, a lawyer obligingly filed a charge of sedition against her.

In such a construct, support for the supreme leader has to be total, and the relationship the leader has with his followers can only be patronising. His conversation with the people becomes one-way. Even Indira Gandhi held durbars, where people came to her home to express their concerns, and like an empress, she would issue orders to fix problems. But she listened to the concerns. Modi speaks often, but listens rarely. His communication, through his radio programme, Mann Ki Baat, is a one-way street. His silences and lack of remorse are eloquent; the time he took to react to Rohith Vemulla's suicide, or to the lynching of Akhlaq, or to the terror spread by gau-rakshaks, or cow vigilantes, is instructive. "There cannot be patricians without plebeians," Eco had noted.

And thus the cult of hero begins. In Brecht's Galileo, Andrea laments – unhappy is the land without heroes, and Galileo responds, no, unhappy is the land in need of heroes. When you lack a hero, you appropriate them. And so fiercely secular leaders like Bhagat Singh and Subhas Chandra Bose, anti-casteist egalitarians like Dr Ambedkar, and iron-willed Congress leaders like Vallabhbhai Patel emerge as icons on the pantheon of the BJP – since it has so few heroes of its own. In Ur-Fascism, Eco wrote, everyone is encouraged to aspire towards becoming a hero. And every soldier who dies is a braveheart or a martyr; even the media uses such terms in its headlines, forgetting the dividing line, if it ever existed, between news and opinion.

The populism of Ur-Fascism is selective; people are only means to an end, numbers to be filled, entities to fill a stadium and rise in chorus, to fill up Rajpath to do a mass yoga exercise. Ur-Fascism changes vocabulary, wipes out the past, creating new myths, and aims to reshape an entire citizenry. Eco concluded:

We must keep alert, so that the sense of these words will not be forgotten again. Ur-Fascism is still around us, sometimes in plainclothes. It would be so much easier, for us, if there appeared on the world scene somebody saying, 'I want to reopen Auschwitz, I want the Black Shirts to parade again in the Italian squares.' Life is not that simple. Ur-Fascism can come back under the most innocent of disguises. Our duty is to uncover it and to point our finger at any of its new instances—every day, in every part of the world…. Freedom and liberation are an unending task.

* * *

The relationship of Indians with freedom of expression is complicated. Indians like freedom of speech for themselves, but not necessarily for those that they disagree with. And the state, whose obligation is to protect the right of free expression, is willing to look the other way when vigilantes protest, giving the vigilantes the courage to act with impunity. So they demand bans, lynching Dalits or Muslims, harass couples on Valentine's Day – and the society, by and large, acquiesces; it tolerates such thuggery. To that extent, India is tolerant of intolerance.

It is worth reflecting on the question: Is tolerance is a desirable virtue. Is it a virtue at all? Tolerance is necessary. A society without tolerance would be at perpetual war with itself, because the alternative is intolerance and its persistence eventually leads to violence. Tolerance implies that the one with power allows others to live their lives the way they wish; the underlying assumption being that there are markers not to be crossed, and those markers may not be defined. (Leaving markers undefined is not an Indian trait; I lived eight years as a foreign correspondent in Singapore, where the government achieved compliance precisely through what were called "OB Markers", or out-of-bound markers, a golfing term. These were never clearly defined, which kept keep journalists, activists, critics, and opponents constantly guessing what they could – or could not – say in public, because one small step that went wrong ensured litigation or prosecution. The system worked.) India isn't there yet, but then the state doesn't have to do anything: its supporters – in the real and virtual world – have been remarkably effective in blunting critics. And the silent majority appears not to care, its silence emboldening the vociferously intolerant.

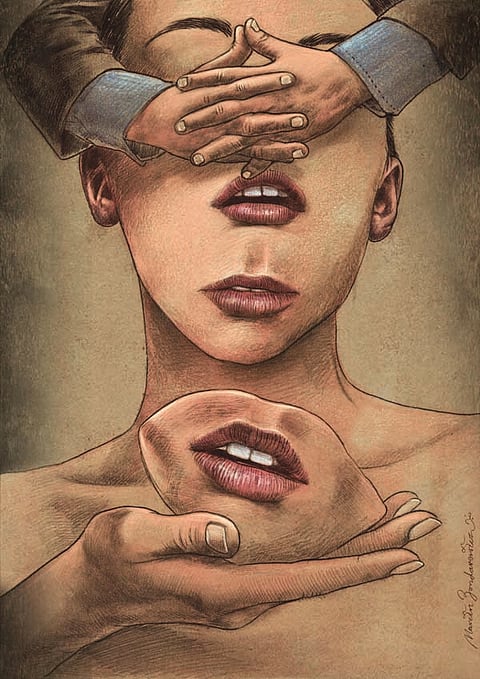

The few who speak up are abused and vilified. In some instances, cases are filed against them. Teesta Setalvad gets raided; Kanhaiya Kumar gets roughed up; Jignesh Mewani gets arrested; Soni Sori gets attacked; Rohith Vemulla's caste status is questioned; and Malini Subramaniam is forced to leave Chhattisgarh. But the dissenting voices are the canaries of the mine. That is the role of the writer, to make us uncomfortable. In Salman Rushdie's The Satanic Verses, the poet Baal says: "A poet's work – to name the unnamable, to point at frauds, to take sides, start arguments, shape the world and stop it from going to sleep." The English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley called poets the "unacknowledged legislators" of the world. At its core, this profund thought represents a simple, powerful truth – the right to dissent.

Great writing shows us what has become of us. The writers who returned state awards last year were trying to stop the Sahitya Akademi from being asleep at the wheel. They also meant to wake us up and show us our face in the mirror, and many of us don't like what we see in the mirror.

But reacting to the number of writers returning the awards, an Indian minister said, surely this is an example of manufactured dissent, scarcely aware of the irony that what the minister wants is what the social critic Noam Chomsky called "manufactured consent".

That virulence aims to bully writers to make them silent. How dare they question or why should they challenge the state? Stuff happens; a writer gets shot; a book gets banned. It is a big country. Such bullying has gone on for years now. A novel – The Satanic Verses – was not allowed to be imported; a writer who fled her own country and sought refuge in India – Taslima Nasreen – felt isolated and often humiliated; a painter – M F Husain – was forced into exile; a rationalist – Sanal Edamaruku – was hounded out of the country; a publisher – Penguin India – withdrew a book because it felt that was the practical thing to do; a novelist – Perumal Murugan – decided to let the writer within him commit 'suicide', saying he won't write fiction anymore, because he was bullied into apologising; and then, a scholar – M M Kalburgi – got shot at his doorstep.

Writers' voices matter; they must have the freedom to speak.

"Things aren't so bad – the intolerant ones are the fringe," we are told.

But what if the fringe becomes the centre?

~ Salil Tripathi is the author of The Colonel Who Would Not Repent: The Bangladesh War and its unquiet legacy and Detours: songs of the open road. He is a contributing editor at Mint and the Caravan in India. He's the chair of the writers-in-prison committee of Pen International. He lives in London.