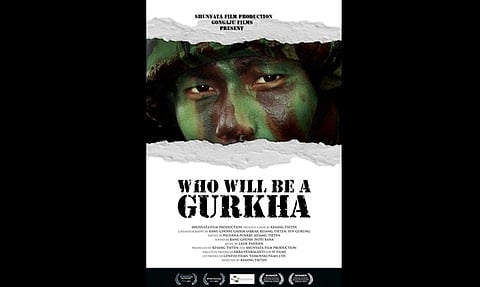

Oriental warriors

The core theme of this film, however, is the very colonial and archaic practice of recruitment that still exists within the Royal Gurkha Rifles regiment of the British army. The film opens with images of young men having their bare chests painted with numbers, followed by recruits having their chests measured, being weighed, having their height measured, sitting in lines on the floor, etc. All of this is interspersed with old, black-and-white archival footage depicting the same recruitment practices. The only change between the present and past appears to be the use of shorts in place of loin-cloths.

In a generous reading of the esprit de corps of the regimental system on the British Army website that claims to maintain "the names, titles and traditions of British Infantry regiments handed down through history", such practices may possibly be valid. However, this takes little away from the fact that these selection processes originated in a racially structured colonial army, based on specific ideologies and mythologies that legitimised them and ultimately aimed to construct a 'Gurkha product' suited for the purposes of the British Empire. It also does little to soften the jarring images of young brown men being 'branded' by the numbers painted on their chests.

Tseten focuses on the most important test in the recruitment process, the doko race. According to the British Army website:

The most gruelling assessment test is known as the doko race. Candidates complete a 2 mile race up a near vertical hill carrying 35kg of rocks in a basket, the weight borne by the traditional Nepalese carrying strap across the forehead. The film begins to build anticipation of this race early, intermittently showing clips of preparations, including dokos being packed and weighed, carried to the race site and set out ready across a green field – a truly stunning image. Contrary to the relatively lighthearted tone conveyed by the website – "It is not for the faint hearted, but the potential recruits will hurtle round the course in only 20 minutes" – the film reveals the men's immense efforts as they struggle to complete the race inside the 45–minutes cut-off time.

Recruitment officials state that the doko race is a "stamina and determination test", but it is unclear why such a test needs to be conducted with a doko, a symbol of Nepali village life. The equivalent physical assessment for other potential British Army recruits appears to be, according to the Army's website, a "150 metre jerry can carry and a 2.4km (1.5 mile) best effort run." The doko's use smacks of an Orientalist imagination still at play. In Nepal today, the extent to which the potential Gurkha recruits – many of whom possess strong English skills and the ability to download information from the British military website – will have carried dokos for any prolonged period of time is questionable. Indeed, earlier in the film one candidate expresses classist sentiments, worrying about being mistaken for a labourer by onlookers during the race.

Furthermore, it is clear that the physicality of the potential recruits is exceedingly important. During the regional selections, potential candidates are almost always seen bare-chested, even during written exams. One Gurkha officer tells a bare-chested candidate, "Stand up like a true Gurkha," before he looks him up and down. There is a particularly telling extended shot of a lone young man standing to attention in shorts while a Gurkha officer stares at his body from various angles for some length of time – there can be no mistake that the man's body is being scrutinised for physical defects that may mar the 'Gurkha product'. Specific age requirements limiting the pool to candidates between the ages of 17.5 and 21 ensure the pick of virile, strong Nepali men. Notably, potential recruits for other forces in the British Army may be aged between 16 and 33 years.

The British Army is afforded the luxury of such attention to detail by the lack of employment opportunities for youth in Nepal, the relatively high earnings promised to selected soldiers, and (now) the opportunity for British Gurkhas to reside in the UK and become British citizens. In the 2011 recruitment process covered by the film, the failure rate was almost 98%: out of 8000 applicants, only 178 were chosen.

Towards the end, the film follows the selected 178 who have, as a British officer declares towards the end, shown themselves "fit and worthy to be soldiers in the Brigade of Gurkhas within the British Army." They receive hair-cuts, put on identical uniforms, practice parade, and lose their individual identities to form a collective social body of Gurkhas. The film ends brilliantly with stark shots of the Nepali men take their oath of allegiance to the British Queen, one hand on a Union Jack-covered table with a large photo of the Queen. The credits roll to a soulful Nepali song to 'Nepal aama' – 'Mother Nepal' – urging her not to cry as her son goes into the army, and vowing to return.

Who will be a Gurkha is an extraordinary film. Tseten has taken full advantage of the access given to him by the British. Still, small critiques can be made. Additional focus on the families of these potential recruits and the preparations undertaken by candidates before entering the camps may have led to a more comprehensive perspective. For instance, an examination of the Gurkha training institutes that have become popular in recent years – institutes that many Gurkha hopefuls see as a must if they want to be competitive– would have added more nuance to the film. But these are minor quibbles.

While the film was screened in mainstream movie halls in Nepal in March 2013, so far it has not furthered debates on foreign soldiering. This could partly be because of the timing of its release: Nepal is going through a prolonged and difficult post-conflict transition, when the politics of government and the upcoming Constituent Assembly elections overshadow other concerns.

Who will be a Gurkha itself takes no stance on ending or continuing the recruitment of Gurkhas. There are, however, political insights and critiques embedded in the dominant narrative structure of the film as it depicts the continuation, in this modern era, of a unique colonial relationship, complete with archaic recruitment practices.

~ Seira Tamang is based at Martin Chautari, a research and policy institute in Kathmandu.