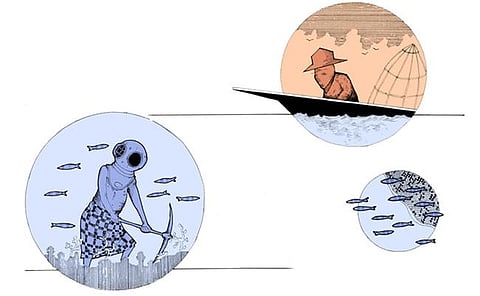

Dividing the spoils

'Bay is Ours,' read the headline of Bangladesh's Daily Star the day after the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) released its verdict on a maritime boundary dispute – the court's first case of the kind – between Bangladesh and Burma. The Bangladeshi press had a rather optimistic interpretation of the ruling, which pertains to some 283,500 square kilometres of the Bay of Bengal. In reality the verdict was a split decision: the tribunal sided with Burma on some issues and with Bangladesh on others. But the verdict gives both countries the green light to pursue their top priority – accessing offshore oil and gas resources in the Bay of Bengal.

Burma and Bangladesh first opened negotiations over their maritime boundary in 1974. They continued talking on and off for almost 35 years, including a two decade break that only ended in 2007. The resumption of talks in the late 2000s came because both countries were anxious to settle the dispute so that each could start offshore exploration for natural gas. Tensions flared in late 2008 when an exploration ship operating under a concession granted by the Burmese government sailed into disputed waters. Bangladesh sent warships to the area, and the exploration ship returned to Burmese waters.

The incident pushed the maritime boundary to the top of the bilateral agenda. The two countries talked frequently through most of 2009, but with little progress. In late 2009 Bangladesh submitted a letter to Burma asking to take the maritime boundary dispute to binding arbitration. Burma responded by asking to petition an unusual decision-making body – the ITLOS. In such disputes, countries most commonly apply to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), but Burma seemed reluctant to go before ICJ for any reason, even a boundary dispute. Bangladesh agreed, and the dispute became the first to be heard by the comparatively less overburdened ITLOS.

Bangladesh feared that the deeply concave shape of the Bay of Bengal would limit its maritime claims to a small wedge-shaped portion of the bay. Burma was fearful that this same concavity would mean a boundary line that unfairly disadvantaged its maritime claims. Both sides worked on their legal arguments and submitted a series of briefs throughout 2010 and 2011, and oral arguments were made in September 2011. After about six months of deliberation, the ITLOS issued a decision that created, after some manoeuvring around coastal features, a line heading southwest (at 215 degrees) away from the coasts of Bangladesh and Burma. Bangladesh was awarded 111,600 square kilometres, or just under 40% of the total relevant area as defined by the ITLOS; Burma was awarded 171,800 square kilometres, just over 60% of the total. While Burma was awarded a larger area, the proportion of awards is largely in line with the length of each country's relevant coastline, in keeping with one of the ITLOS's key criteria for determining if a ruling is fair.

Drills at the ready

The tribunal's ruling can be seen as a partial victory for both sides. The court adopted Burmese arguments on the major principle for drawing the boundary line, drawing a line equidistant from the points nearest to it on both the Burmese and Bangladeshi coastlines, and then adjusting that line for relevant circumstances. The court also agreed that the location of St Martins Island, a Bangladeshi possession further south than any point on the Bangladeshi mainland, should not significantly impact the position of the dividing line. Bangladesh also won several legal battles; most importantly, the court ruled that interpreting international law as Burma advocated would produce what it called a 'cut-off' effect, or a line that would unfairly cut Bangladesh off from its natural seaward projection. The ITLOS considered this a special circumstance, and consequently adjusted the equidistant line in Bangladesh's favour.

The ruling also created a grey zone – an area in which, by the peculiarities of international law, both states were awarded partial jurisdiction. The area lies on the Bangladeshi side of the final dividing line, but is closer to the Burmese coast, which means that Bangladesh cannot claim the same rights in this area as Burma. As a result, the court left the sovereignty of the area undecided, giving Bangladesh rights to seabed resources such as oil and gas, and Burma fishing rights and all other privileges associated with exclusive economic zones (which normally stretch up to 200 nautical miles from a country's coast).

Bangladesh wasted little time in taking advantage of its new maritime territory. ConocoPhillips, the American multinational energy corporation which received exploration rights to two partially disputed blocks of the area in 2009, was notified the day after the ruling that it could begin exploration. The company, apparently bullish on its prospects for oil and gas finds, subsequently asked the Bangladeshi government to grant it exploration rights in six additional blocks it had bid on in 2009. The Bangladeshi government was also keen on a symbolic show of sovereignty over its new possession – within a week of the ruling, the Bangladesh Navy sailed a vessel just along the inside of the new boundary line.

Burma's government is also auctioning off new offshore oil and gas blocks, and should complete the process this year. But unlike past natural gas finds, Burma's new discoveries may no longer be destined for the export market. According to Burma's Minister of Energy, once the two offshore gas projects – the Shwe and Zawtika – currently under development come online, future discoveries will be used to supply the domestic market.

India, the other claimant of large parts of the Bay of Bengal, was paying close attention to the boundary dispute. India also has a boundary dispute with Bangladesh pending arbitration. The boundary drawn by the ITLOS between Bangladesh and Burma has created a new legal precedent by extending jurisdiction past the customary limit of 200 nautical miles from a country's coastline and onto the continental shelf. Though the ruling does not directly affect India as the line is only valid "until it reaches the area where the rights of third States may be affected", the new legal precedent could be cause for concern in future rulings and disputes. Shortly after the ITLOS ruling, India asked Bangladesh to forego the ongoing arbitration and pursue a bilateral settlement, but Bangladesh rebuffed the offer.

The orderly, peaceful and relatively equitable resolution of the maritime boundary marks a decidedly more positive note in the Burma-Bangladesh relationship, and removes a key obstacle that could have stalled greater economic engagement. While several difficult issues – the status of the Rohingya people, for instance – remain unresolved, the maritime boundary case proves that the two countries can cooperate and find mutually agreeable solutions on issues of common interest. In this case, the newly established maritime boundary opens up much of the Bay of Bengal to offshore energy exploration, which should greatly benefit both nations.

~ Jared Bissinger is currently completing a doctoral degree focusing on the Burmese economy at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia.