Representing risks

In 2013, a leading British medical journal the Lancet published a research report about the risk factors for congenital abnormality. Congenital anomalies, also known as birth defects, are structural deformities that develop in the uterus or arise from birth or neonatal trauma. Although 'congenital' implies 'inborn', these anomalies are not always genetic in origin, but have chromosomal, genetic and environmental causes. The article was based on analysis of data from a multi-ethnic cohort of 13,776 babies born in Bradford, Yorkshire, between 2007 and 2011. The authors were interested in understanding why there are ethnic differences in rates of congenital anomaly. They sought to identify associations with known risk factors, specifically poverty, maternal age, educational level, parental consanguinity, alcohol consumption and smoking behaviour.

Such questions are particularly significant in Bradford, one of the UK's poorest cities, and home to around ten percent of England's Pakistani Muslim population. In the UK overall, rates of infant death and childhood illness are highest in babies of Pakistani ethnicity, and most of this mortality and morbidity is due to congenital anomalies. The Bradford researchers found that, according to the study, the highest proportion of congenital anomalies were seen in the 5127 babies born to Pakistani parents. They also observed that 60 percent of the Pakistani babies had parents who were consanguineous – related as second cousins or closer – and 37 percent had first-cousin parents. In the analysis of risk factors, parental consanguinity was associated with about one-third of the anomalies in Pakistani babies. Overall, it doubled the two percent background risk for congenital anomaly, and its effect was independent of poverty. This risk level was determined to be similar to the risk associated with mothers of white British origin over 34 years old.

To a paediatrician or clinical geneticist working in Bradford these observations would probably not be surprising. For over two decades, clinicians working in areas of substantial Pakistani settlement have been observing more metabolic and neurodegenerative developmental problems in babies born to Pakistani parents than in white British babies. The new study confirmed this observation. A higher frequency of birth defects has often been attributed to the elevated risk of recessive genetic conditions – many of them very rare – associated with parental consanguinity. In medical circles at least, this risk is well known, and was reported in a number of earlier British studies. In 1993, for instance, a similarly elevated risk for birth defects associated with parental consanguinity was reported from a five-year prospective study of nearly 5000 babies born in Birmingham, in the Midlands, which also has a substantial Pakistani population.

The cousin marriage question

One of the reasons why a new study was important is that, despite the earlier evidence, there has been continuing scepticism over the meaning and implications of the link between parental consanguinity and birth defects. This scepticism has prevailed both within sections of the Pakistani population and outside of it, particularly among those aware of stereotypically negative and racist attitudes towards non-white minorities. Intense controversy has raged in public debates since the 1990s over this issue. Critics have argued that the high rates of infant death and long-term illness in Pakistani children could equally be caused by poverty, unequal access to prenatal care for mothers, low rates of abortion of severely affected foetuses, poor quality obstetric experiences and other developmental or environmental factors. It would therefore be necessary to examine parental consanguinity alongside the other factors associated with adverse birth outcomes, including racism in service delivery to a disadvantaged minority group. Without a more rounded picture, the clinical attention to "consanguinity and related demons", as Waqar Ahmad argues in his 1996 essay on science and racism in the debate on birth outcomes, becomes a new racism by pathologising a minority cultural practice.

Cousin marriage in the public imagination has indeed come to symbolise fundamental differences between the majority white British and the Pakistani British minority – and, to some extent, other minority groups that practice consanguineous marriage, such as Bangladeshis, Moroccans, Turks and Arabs, although they have received considerably less public attention. The perceived differences pertain mainly to practices of kinship and marriage, gender norms and religion. Since 11 September 2001, against a backdrop of growing anxieties about security, the media narrative has shifted from cousin marriage being an Asian or Pakistani practice to it being 'customary' among Muslims. As the Daily Mail declared: "Marriage between cousins in Muslim communities is causing terrible disabilities in children."

These statements do not acknowledge the ethnic and religious diversity of people who practice cousin marriage globally or even within the UK more specifically. Certain Jewish, Christian and Hindu groups practice it. Among Muslims there is diversity in marriage patterns and in religious opinion about the desirability of close-kin marriage. The ethnographic literature on British Pakistanis shows there is increasing diversity in marital forms, and provides nuanced documentation of the complex emotional and strategic dimensions of transnational arranged marriage, and of how perceptions of the balance of risks involved have changed. But in dominant public representations, cousin marriage has instead become a vehicle for expressing a range of racial anxieties.

One such concern is the forced marriage of young British adults to partners usually from overseas. Spousal immigration is now the only form of family reunification still available to many British citizens of foreign origin, and so it has strategic significance within many transnational families, particularly where marriages are conventionally arranged within or outside the family. According to recent estimates, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh together provide around one-third of all spouses granted settlement in the UK – some of these involve consanguineous kin, and some do not. A proportion of these transnational marriages are forced, in that the marriage is contracted without the individual's freely given consent.

But in most debates the distinctions between cousin marriage, arranged marriage and forced marriage are quickly blurred, such that all arranged marriages are assumed to be coercive to some degree, especially if the spouse is a relative. In the state secondary school they attended, for example, my children were taught that a cousin marriage is a marriage forced upon young people by their parents. If you add to this conflation of arranged marriage with forced marriage the spectre of inbreeding and birth defects, you have a particularly powerful set of negative images. In 2005, Ann Cryer, then-MP for Keighley in Yorkshire, who has successfully campaigned against forced marriage, called for the government to consider making cousin marriages illegal: "Anyone who seeks to excuse the passing on of terrible illness due to cultural traditions needs to know that that sort of culture is unacceptable in the twenty-first century."

Not only this, but cousin marriage is also often regarded in such public statements as directly inhibiting the assimilation of minority groups. Khola Hasan has written about how consanguineous marriage in the Mirpuri community has been perceived as hindering integration and discouraging "contact with the wider community", and how such a "high degree of insularity" can create "moist ground for breeding radical thought". Some of the most sweeping statements go so far as to link cousin marriage with a monolithic idea of the Muslim kinship structure in which, in the words of Stanley Kurtz (a conservative commentator in the US), lies "an unexamined key to the war on terror".

On political correctness

Another feature of recent coverage on the topic of cousin marriages and birth defects among Pakistanis is to claim that a culture of 'political correctness' has led to a failure in addressing these issues adequately. "It's time to confront this taboo" the Mail on Sunday headline ran, since "multicultural Britain" has made it controversial to talk about how "marriage between cousins in the Muslim communities [has] left hundreds, if not thousands, of children damaged or dead." Political correctness in the context of British multiculturalism is seen as a pressure not to criticise any aspect of minority ethnic culture because to do otherwise causes offense and invites the accusation of racism.

In these ways, much of the reporting of the issue of genetic risk in cousin marriage has been generalised to other issues such as forced marriage, and politicised within debates about race, anti-racism, multiculturalism and integration. It is still all too common for Pakistani families and health staff either to deny the risk, or else to assume that parental consanguinity is the underlying cause of every illness or disability in a Pakistani infant. And because the issue is experienced through a politics of prejudice, it is extremely difficult for the risk information to be taken seriously, even by parents with children diagnosed with recessively inherited genetic conditions.

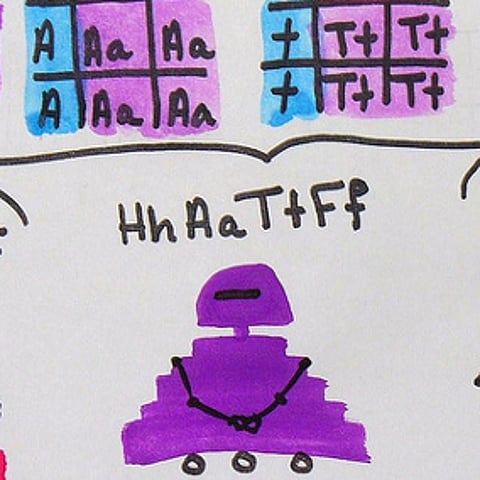

A British layperson is likely to accept uncritically the association between parental consanguinity and birth defects; after all, the observation in contemporary Britain today applies to a minority marriage pattern. But in the Pakistani populations where I have worked, it is common for a layperson unfamiliar with genetics to respond to the discourse of genetic risk in cousin marriage by making the perfectly accurate epidemiological observation that there are plenty of Pakistani people married to cousins who have children who are perfectly healthy, and there are many English people who do not marry cousins who may still have children with disabilities. So how, this critique runs, can disabilities in Pakistani children have anything to do with cousin marriage? Recessive inheritance is difficult to grasp without some expertise in genetics. Everyone is an unaffected carrier of a number of conditions from which they don't suffer themselves, and if their partner is also an unaffected carrier of the same condition – a situation that parental consanguinity makes more likely – they have a 75 percent chance of having an unaffected child, and a 25 percent chance of having an affected child each time they conceive.

A large part of the problem arises from how the risk is presented. In media reporting, it is frequently presented as a 'doubled' risk. In absolute terms, this amounts to a risk of between four and six percent of having an affected child, which is twice the two to three percent risk for unrelated couples. Put another way, this amounts to a 90 to 94 percent chance of having an unaffected child. If there is a history of consanguineous marriages in the family, the risk is roughly tripled. Genetic counselling is available in the UK for couples worried about these risks, especially where there is a history of genetic illness in the family. By analysing family history to identify any genetic illness in the family, and by offering genetic carrier tests, genetic counsellors can provide couples with more precise risk estimates. On the basis of DNA analysis of parental blood samples, clinicians may sometimes entirely rule out the risk for a particular condition identified in the family history, and they will offer couples at risk a range of options for managing future pregnancies.

Perhaps more importantly, the focus on cousins in the presentation of risk for recessive genetic conditions is misleading. With recessive inheritance, the important thing to establish is whether both partners carry the same genetic mutation. If they are carriers of the same mutation, then they have a 25 percent risk of having an affected child each time they conceive. Being cousins makes this situation more likely, because each partner might inherit the same mutation from a shared grandparent. But marriage partners can inherit a mutation in the same gene without being cousins, particularly where marriages take place over generations within kinship groups such as the biradaris, with which most Pakistanis identify. What matters in the context of genetic risk is the genetic carrier status of the partners, not the degree of social relatedness, and carrier status can be established through genetic counselling and carrier testing for an increasing number of known recessive conditions.

One among other factors

The media presentation of genetic risk rarely acknowledges that parental consanguinity is just one among other risk factors for congenital abnormality. An important feature of the article in the Lancet is that it examined a range of risk factors for birth defects, not just the association with parental consanguinity. By examining how these factors were similar and different across ethnic groups, the authors aimed to reduce as far as possible the stigmatising of Pakistanis. They found, for example, that across all ethnic groups, mothers who were educated to diploma or degree level, or equivalent, were less likely to have babies with abnormalities than less educated mothers, although they did not speculate on the reasons for this association. They also found a doubled risk for congenital abnormality among white British mothers older than 34 years. This effect was not observed for the Pakistani mothers, since the Pakistani babies with anomalies were mostly born to younger mothers.

There is an interesting comparison to be made between reactions to the approximately equivalent risks for anomalies in babies born to mothers over 34, and the risk for anomalies associated with parental consanguinity. No politician has ever suggested that women over 34 should not be allowed to marry or should be strongly discouraged from reproducing because they are twice more likely than younger women to have children with birth anomalies. To make this argument would undoubtedly be seen as an attack on individual freedom. Rather, such women are encouraged to make full use of prenatal screening and counselling in the management of their pregnancies.

Before the article in the Lancet was published, there had been several radio programmes about the larger study from which the article's data on congenital abnormality were drawn. The Born in Bradford (BiB) project is an ongoing prospective-birth-cohort study monitoring the health of babies and families over a period of 30 to 40 years. It aims to shed light on the early indications of childhood illness and longer-term health problems, such as diabetes and obesity, by monitoring the associations with biological indicators and social factors, such as lifestyle and socioeconomic status.

One of the broadcasts about the project in April 2012 reported that in a sample of 2000 mothers, of whom half were Southasians, a small number of cot deaths occurred to babies of white mothers. Cot death, or crib death, is the popular name for the sudden, unexpected death of an infant less than a year old for which there is no adequate medical explanation even after postmortem investigation. Most often the baby dies in his/her sleep – usually in their cot. "Asian babies do not have cot deaths because they are not put in cots," the Bib project's director John Wright commented, adding that "Asian women's instincts [to sleep with their babies] are right… Educated white women [also] sleep with their babies. The danger is where parents drink and smoke and sleep on the sofa." It was therefore wrong, he commented, that Asian women had been put under pressure not to bed share: "not all co-sleeping is the same."

Those involved in the Born in Bradford project hope that it will now be easier to discuss openly the genetic risks in cousin marriage and, therefore, easier for clinicians to provide individuals and families with prenatal counselling and non-invasive screening if appropriate. But the very fact that the risk has been identified via ethnicity, which is sometimes a way of talking about cultural difference, makes it very difficult to avoid stigmatising Pakistanis. Headlines reporting on the Bradford study in the Guardian and the Independent last year ran the usual presentation of statistics: marriage between first cousins "doubles risk of birth defects", while the Daily Mail headline highlighted ethnicity: "Warning over cousin marriages: Unions between blood relatives in Pakistani community account for third of birth defects in their children".

While it is important to be critically aware of the biases in media representations of cousin marriages among British Pakistanis, the report in the Lancet provides important information about the genetic risks in consanguineous partnerships, showing an effect of parental consanguinity that is independent of socioeconomic status. As the authors conclude, the identified risks need to be incorporated into sensitive and accurate public-health messages within communities where consanguineous marriage is practised. In short, what is needed is better information and counselling to manage pregnancies and inform lifestyle choices, rather than berating a community for its 'cultural' practices.

~Alison Shaw is a professor of social anthropology at the University of Oxford. Her publications include Kinship and Continuity: Pakistani families in Britain (Routledge/Harwood 2000); and, with Aviad Raz, the forthcoming Cousin Marriages: between tradition, genetic risk and cultural change, among others.

~This article was first published in December 2014.